Information about the city. Panorama Susaninskaya Square

Ekaterinoslavskaya square,

Revolution square

Susaninskaya square- the central square of the city of Kostroma. Arose according to the regular plan of Kostroma 1781-1784. The development of the square is an integral, exemplary of its kind, architectural ensemble of the late 18th-19th centuries.

History

The area originated under the name Ekaterinoslavskaya according to the regular plan of Kostroma 1781-1784. Before the fire of 1773, since 1619, the territory of the New City of the Kostroma Kremlin was located in its place, and before its construction - the urban settlement. The construction of the area was carried out at the end of the year. XVIII - 1st Thursday XIX century. Initially, the configuration of this area was conceived to be semicircular, but when implemented, it received a "faceted" shape.

In 1823 the square was paved, and in 1835 by the decree of Nicholas I it was renamed from Ekaterinoslavskaya to Susaninskaya.

In 1918, the destruction of the Susanin monument began, at the same time it was renamed into Revolution square... In 1924, the Alexander Chapel was demolished, and on a part of the square between the Red and Bolshoy Flour Rows, a sports ground was set up, and then a public garden. In 1967, a new monument to Ivan Susanin was erected in the park on the site of the chapel (sculptor N. A. Lavinsky).

The historical name was returned to the square in 1992. In 2008-2009. A large-scale reconstruction of the square was carried out: trees in the center of the square were cut down, lawns were laid, pedestrian paths were laid, elements of small architecture were laid. A temporary memorial sign has been erected at the site of the historical monument to Ivan Susanin.

Currently, the area is used for organizing city festivals. In 2009 and 2010. the operas Boris Godunov and Khovanshchina (a joint project of the New Opera and the Regional Philharmonic Society) were staged on the square.

Buildings and constructions

Kostroma main square.JPG

View of Susaninskaya Square before reconstruction (2005)

Hauptwachta-kostroma.jpg

The building of the former guardhouse

Kostroma Downtown.jpg

House of General S. S. Borshchov

Thumbnail creation error: File not found

Monument to Ivan Susanin (1967)

Transport

The radial-semi-circular layout of the historical part of Kostroma has led to the fact that a significant part of traffic flows in the center crosses Susaninskaya Square. The movement of transport on the square is organized by two streams: Sovetskaya Street - Tekstilshchikov Avenue and Simanovsky Street - Lenin Street - Mira Avenue - Shagova Street - Sverdlov Street. There are public transport stops on the square: bus, trolleybus and fixed-route taxis.

- In honor of Catherine II, the square was named Yekaterinoslavskaya. The main axis of the city planning, which runs perpendicular to the Volga embankment - Pavlovskaya Street - is named after the son, the future Emperor Paul I. Four more rayon streets were named in honor of the empress's grandchildren and granddaughters - Aleksandrovskaya, Konstantinovskaya, Mariinskaya and Yeleninskaya.

- The area in everyday life among Kostroma residents is called “ frying pan».

Write a review on the article "Susaninskaya Square"

Links

- Bochkov V.N.

Literature

- E.V. Kudryashov The architectural ensemble of the center of Kostroma. - Kostroma, 1993 .-- 64 p .; ill.

Notes (edit)

Excerpt from Susaninskaya Square

“I think, however, that there is a basis in these condemnations as well…” said Prince Andrey, trying to fight against the influence of Speransky, which he was beginning to feel. It was unpleasant for him to agree with him in everything: he wanted to contradict. Prince Andrey, who usually spoke lightly and well, now felt the difficulty of expressing himself when speaking with Speransky. He was too interested in observing the personality of a famous person.“There may be a basis for personal ambition,” Speransky put in his word quietly.

“Partly for the state,” said Prince Andrew.

"How do you understand? ..." said Speransky, quietly dropping his eyes.

“I am an admirer of Montesquieu,” said Prince Andrew. - And his thought that le rrincipe des monarchies est l "honneur, me parait incontestable. Certains droits еt privileges de la noblesse me paraissent etre des moyens de soutenir ce sentiment. [The basis of monarchies is honor, it seems to me unquestionable. Some rights and the privileges of the nobility seem to me to be the means to maintain this feeling.]

The smile disappeared on Speransky's white face, and his physiognomy benefited a lot from this. Probably Prince Andrew's thought struck him as entertaining.

- Si vous envisagez la question sous ce point de vue, [If you look at the subject like that,] - he began, pronouncing French with obvious difficulty and speaking even more slowly than Russian, but quite calmly. He said that honor, l "honneur, cannot be supported by advantages detrimental to the course of service, that honor, l" honneur, is either: the negative notion of not doing reprehensible acts, or a known source of competition for approval and rewards expressing it.

His arguments were succinct, simple and clear.

The institution that upholds this honor, the source of competition, is an institution like the Legion d "honneur [Order of the Legion of Honor] of the great emperor Napoleon, not harming, but promoting the success of service, not class or court advantage.

- I do not argue, but it cannot be denied that the court advantage has achieved the same goal, - said Prince Andrey: - every courtier considers himself obliged to bear his position with dignity.

“But you didn’t want to take advantage of it, prince,” said Speransky, showing with a smile that he, an awkward argument for his interlocutor, wishes to end it with courtesy. “If you do me the honor of welcoming me on Wednesday,” he added, “after talking with Magnitsky, I will tell you what may interest you, and besides, I will have the pleasure of having a more detailed conversation with you. - He closed his eyes, bowed, and a la francaise, [in the French manner,] without saying goodbye, trying to be unnoticed, left the hall.

During the first time of his stay in St. Petersburg, Prince Andrey felt his entire mentality, developed in his solitary life, completely overshadowed by those petty concerns that gripped him in St. Petersburg.

Returning home in the evening, he wrote down 4 or 5 necessary visits or rendez vous [dates] in a memorable book at the appointed hours. The mechanism of life, the order of the day such as to keep up with time everywhere, took away a large share of the very energy of life. He didn’t do anything, didn’t even think about anything and didn’t have time to think, but only spoke and said with success what he had time to think over in the village.

He sometimes noticed with displeasure that it happened to him on the same day, in different societies, to repeat the same thing. But he was so busy all day long that he didn’t have time to think about the fact that he was not thinking anything.

Speransky, both on his first meeting with him at Kochubei's, and then in the middle of the house, where Speransky, having received Bolkonsky, talked to him for a long time and trustingly, made a strong impression on Prince Andrey.

Prince Andrey considered such a huge number of people to be despicable and insignificant creatures, so he wanted to find in another a living ideal of the perfection to which he strove, that he easily believed that in Speranskoye he had found this ideal of a completely reasonable and virtuous person. If Speransky was from the same society that Prince Andrey was from, the same upbringing and moral habits, then Bolkonsky would soon have found his weak, human, non-heroic sides, but now this logical mindset, strange for him, inspired him all the more respect that he did not quite understand him. In addition, Speransky, whether because he appreciated the abilities of Prince Andrei, or because he found it necessary to acquire him for himself, Speransky flirted before Prince Andrei with his impartial, calm mind and flattered Prince Andrei with that subtle flattery, combined with arrogance, which consists in tacit recognition his interlocutor with himself is the only person who is able to understand all the stupidity of everyone else, and the rationality and depth of his thoughts.

During their long conversation in the middle of the evening, Speransky said more than once: "We look at everything that goes beyond the general level of an ingrained habit ..." or with a smile: "But we want the wolves to be fed and the sheep safe ..." or : "They cannot understand this ..." and everything with such an expression that said: "We: you and me, we understand what they are and who we are."

This first, long conversation with Speransky only strengthened in Prince Andrei the feeling with which he first saw Speransky. He saw in him a reasonable, strictly thinking, enormous mind of a man who, with energy and persistence, had attained power and was using it only for the good of Russia. In the eyes of Prince Andrey, Speransky was precisely that person who rationally explains all the phenomena of life, recognizes only that which is reasonable as valid, and who knows how to apply the standard of rationality to everything, which he himself so wanted to be. Everything seemed so simple, clear in Speransky's presentation that Prince Andrei involuntarily agreed with him in everything. If he objected and argued, it was only because he wanted to be independent on purpose and not completely obey Speransky's opinions. Everything was so, everything was fine, but one thing embarrassed Prince Andrei: it was Speransky's cold, mirrored gaze that did not let into his soul, and his white, gentle hand, which Prince Andrei involuntarily looked at, as people usually look at. with power. For some reason, the mirrored look and this gentle hand irritated Prince Andrew. Prince Andrey was unpleasantly struck by the still too great contempt for people, which he noticed in Speransky, and the variety of methods in the evidence that he cited in support of his opinions. He used all possible tools of thought, excluding comparisons, and too boldly, as it seemed to Prince Andrew, passed from one to another. Either he stood on the basis of a practical figure and condemned dreamers, then on the basis of a satirist and ironically laughed at his opponents, then he became strictly logical, then suddenly he rose into the field of metaphysics. (He especially often used this last instrument of evidence.) He transferred the question to metaphysical heights, passed on to the definitions of space, time, thought, and, bringing forth refutations from there, again descended to the ground of dispute.

In general, the main feature of Speransky's mind, which struck Prince Andrei, was an undoubted, unshakable faith in the strength and legitimacy of the mind. It was evident that Speransky could never have thought of that usual idea for Prince Andrei that it was impossible to express everything that you think, and there never came a doubt that all that I was thinking and all that was nonsense. what do I believe in? And this particular mentality of Speransky most of all attracted Prince Andrei.

The first time of his acquaintance with Speransky, Prince Andrei had a passionate sense of admiration for him, similar to that which he once experienced for Bonaparte. The fact that Speransky was the son of a priest, who could have been stupid people, as many did, went to despise as a shopkeeper and priest, forced Prince Andrei to treat his feelings for Speransky with particular care, and unconsciously strengthen it in himself.

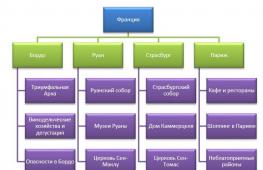

Center of Kostroma- This is a huge Susaninskaya Square, which is spread out on both sides of Sovetskaya Street. Its northeastern part is affectionately called "Frying Pan" by the people.

The development of the square is a unique, exemplary of its kind, architectural ensemble of the late 18th-19th centuries. In the very center, by analogy with other regional centers, there is Prime Meridian.

The historical part of Kostroma has a radial-semicircular layout - streets depart from Susaninskaya Square in different directions, like rays of the sun. There is a legend that Catherine II, when asked what she would like to see Kostroma, unfolded her fan. So the streets were built according to the empress's fan-shaped layout. To this day, if you look at Kostroma from a height, it seems that there is a huge fan.

Most public transport routes pass through Tekstilshchikov Avenue. There is a trolleybus in Kostroma. But the main carrier is route taxis. The minibus is the main sign of problems with public transport in the city.

Public transport in Kostroma - Trolleybus

Every year, magnificent flower gardens are planted on Susaninskaya Square. In the center of the city, patterns of thousands of dahlias, petunias and cineraria appear.

And in 2014, not far from the monument to Susanin, an interesting flower garden in the shape of a boat was erected, which Kostroma kids and tourists love to climb.

Alongside the monument to Susanin, in the center there is a "small architectural form" for the fire dog Bobke. This dog in the 19th century lived in the fire department and saved lives. Near the monument there is a ball - a piggy bank, where everyone can throw a coin as a donation to the City Center for Overexposure of Animals.

To the left of the square, in Bolshoi Flour Rows, there is a cheese exchange where you can buy products from the manufacturer. Cheese production is one of the main brands of Kostroma. In general, there is hardly another such city in Russia with so many well-known brands. Here is an incomplete list: "The cradle of the Romanov dynasty", "Ivan Susanin - a patriot of the Russian land", "Kostroma - the pearl of the Golden Ring of Russia", "Kostroma - the Small homeland of A.N. Ostrovsky "," Kostroma - the flax capital of Russia "," Kostroma - the jewelry capital of Russia "," Kostroma - the cheese capital of central Russia ".

Kostroma is the cheese capital!

Below we will tell you in detail about the most important sights of the central part of Kostroma.

Kostroma architecture

On the Susaninskaya Square of Kostroma, there are administrative and commercial ensembles, which are among the best examples of Russian provincial classicism of the 18th-19th centuries. They were erected by St. Petersburg craftsmen in accordance with the special "imperial status" of the city, which is why Kostroma is sometimes compared to St. Petersburg.

On the panorama of Susaninskaya Square (from left to right) - the Fire Tower, the former guardhouse, the former house of Rogatkin and Botnikov, Borshchov's house and the Building of Public Places.

An outstanding monument of the era of classicism - a 35-meter fire tower has long been an architectural symbol of Kostroma and the highest point in the city center. Arriving here in 1834, Emperor Nicholas I exclaimed enthusiastically: “I don’t even have such a tower in St. Petersburg”... Until the 1990s, it remained an active fire department, now transferred to the Kostroma Museum.

Former guardhouse

In the vicinity of the fire tower in Kostroma, there is the building of the former garrison guardhouse. Today the building is occupied by a branch of the Kostroma State Historical, Architectural and Art Museum-Reserve. Architect P.I. Fursov is the author of these two small architectural masterpieces of the imperial level.

Former house of Rogatkin and Botnikov

Center of Kostroma. Left - Former house of Rogatkin and Botnikov

A three-storey brick building in the classicism style (pictured on the left) is the most unobtrusive of the architectural ensemble of Susaninskaya Square. But despite its plainness, the building continues to play an extremely important urban planning role in the ensemble of Susanin Square. Not to mention the historical significance - it was in this house that A.N. Ostrovsky himself lived and the "moral genius" of Russian literature V.G. Korolenko.

Borshchov House

Borshchov's mansion N.I. Metlina- This is one of the largest estates in Kostroma of the first quarter of the 19th century, which has an extremely important urban planning significance in the development of the center.

It was in this house that Nikolai Nekrasov, observing scenes from city life, described the monument to Tsar Mikhail Romanov and the peasant Ivan Susanin that stood on Susaninskaya Square until 1918 in his poem "Who Lives Well in Russia":

It stands forged of copper,

Just like Savely

granddad,

A man in the square

- Whose monument? -

Susanina

Building of Public Places in Kostroma

One of the main administrative and public buildings of Kostroma is located at Sovetskaya, 1. In the past - Official places, now - the city administration. The building was created according to the model project of the famous Russian architect A.D. Zakharova. Similar administrative buildings can be seen in other cities of Russia, since the project is typical.

Cheese exchange in Kostroma

The Cheese Exchange is located to the left of the square, in Bolshoi Flour Rows, Pavilion No. 53

In a political sense, Kostroma was called the capital for a short time, but to this day it proudly carried the title of the cheese capital.

At the end of the 19th century, merchant Vladimir Blandov founded the first cheese factory on the Kostroma land in the village of Andreevskoye. In those days, cheese was a rare and expensive delicacy and was rarely available to the common people. But after a while, it began to be produced on an industrial scale throughout Russia.

Today in the Kostroma region there are about 11 large cheese factories that produce the well-known varieties "Kostromskoy", "Susaninsky", "Demidov", "Voskresensky", "Ivan Kupala".

If you are in Kostroma, be sure to check out the Cheese Exchange, which is located on Susaninskaya Square on the Volga side. Here you can try all the variety of Kostroma cheeses, and buy the product you like at the manufacturer's price.

Monument to Ivan Susanin in Kostroma

Initially, the monument to Susanin stood on Susaninskaya Square, opposite the fire tower. In the center of the composition was a bust of Mikhail Romanov, at the foot of which was the figure of the patriot Ivan Susanin. It was demolished by the Bolsheviks, who considered such a position humiliating for the national hero.

The modern monument to Ivan Susanin meets tourists at the Trading Rows on Molochnaya Gora street.

Our next excursion is dedicated to the streets of Kostroma. We will walk along the central boulevard, Tekstilshchikov Avenue, Simanovskiy and Sovetskaya streets.

A couple of centuries ago, not only this area did not exist, but the territory occupied by it did not look like it does today. Then it was cut by the Sula River, which flowed near the modern building of the regional court and laid a channel in the northwest direction. On the left bank of the Sula, wooden walls with towers and gates of the Kostroma fortress stood on a rampart - the so-called. "New town", built in 1619, behind which the marketplace was noisy, on the right - the garden of the landowners Borshchov, hay bargaining and, to the north, the apple orchard of the Volkov merchants.

Clark V.N. View from the fire tower towards the house of Botnikov and Rogatkin. 1905 g.

In 1773, a fire destroyed the fortifications of the "New City" - they, as unnecessary, were no longer restored. When drawing up the plan of Kostroma, experienced St. Petersburg architects took into account the benefits of this place at the junction of two traditional city "ends" in the immediate vicinity of the Volga and made an important decision - it is here to plan the main square of the city. Previously, for this it was necessary to enclose Sula in solid oak logs and hide it under the ground and tear down the earthen ramparts of the "New City". The square was designed as a polyhedron, open towards the Volga, seven radial streets were drawn to it, while the eighth was a sloping and wide descent to the river.

The formation of Yekaterinoslavskaya Square, named after the then Russian Empress Catherine II, began in the second half of the 1780s. It was created by a whole galaxy of talented architects who worked with a highly developed sense of continuity, who appreciated the heritage of their predecessors, who strove to comprehend their creative ideas and erect a single architectural ensemble on the square.

Susaninskaya (Ekaterinoslavskaya) square

The first of these architects was Stepan Andreevich Vorotylov (1741 -1792). He was born in the settlement Bolshie Soli of the Kostroma district in the family of a poor bourgeoisie. During his life, driven by curiosity, he changed many professions, in each of which he achieved perfection: from childhood he was engaged in fishing with his father, then he tailored, mastered the blacksmith's craft, then decided to “stone work”. “Diligently delving into his duty,” recalled a contemporary and fellow countryman Vorotilov, “he himself learned to draw and draw plans, finally, about the thirtieth year of his life by natural attraction without the help of outside teachers and mentors, by himself, with attention reading geometry and algebra , I learned architecture, which I managed to do and improved myself very much in my own practice. " This nugget carried out large-scale construction work according to his own projects, not only in Kostroma and its suburbs, but also in Yaroslavl, Ryazan, etc. “As for his character,” the biographer continued, “he was the only person of his kind ... From his deeds, honesty and disinterestedness are very visible. He treated the workers meekly and favorably, he calculated them well. Going round his contracts and works that had been in different places, and seeing a malfunction in the work, he repeatedly ordered to break it with him, although at his own expense the change again. He lived in the circle of his family, as befits a reasonable master, to whom all the household willingly obeyed. "

Gostiny Dvor (Red Rows)

Indeed, the buildings of the tycoon are distinguished by a special quality factor. Stepan Andreevich took over the construction Gostiny Dvor, which consisted of two stone commercial buildings, which laid the foundation for the development of the square and outlined it from the Volga side. For centuries, Kostroma was a major center of Russian trade. In the XVII century. there were 714 stores in it, forming 21 trading rows, and 148 stores were scattered around. Such a significant number of trading premises, of course, could not fit in the "New City" - some of them huddled under the city walls and along the slope of Molochnaya Gora. Almost all the shops burned down in 1773, merchants temporarily built all kinds of shelves, etc., which were demolished as the stone rows were built.

The basis was the "exemplary" project of shopping malls, signed by the Vladimir provincial architect Karl Clair... Construction began in 1789. When building the left (if you face the Volga) building of the Gostiny Dvor, Vorotylov had to solve the problem of how to fit the Church of the Savior into it. This church, one of the oldest in Kostroma, was originally wooden, and in 1766 a stone temple was erected in its place. Until the end of the 17th century. the church stood on the churchyard, which was then moved to the end of Rusina Street (now Oktyabrskaya Square), and a garden was planted near the temple, and the temple became known as "Savior in the Gardens" (the bell tower of this church, which significantly enriched the silhouette of the entire square, was built at the beginning of the 19th century. local self-taught architect A.V. Krasilnikov).

The construction of the left wing, also called the “Red Rows,” since it was used to trade in “red” goods (fabrics, leather goods, furs, even books), proceeded fairly quickly. In March 1791, the city council announced that 33 shops were ready, 19 were being completed, and materials had been prepared for 11 - a total of 86 shops were supposed to be located in the building. The work was completed by 1793.

The construction of the right building, called the "Big Flour Rows", was built more slowly - in 1791, out of 52 projected shops intended for wholesale and retail trade in flour, fodder and flax, 26 were roughly finished. Petersburg grandee Count A.R. Vorontsov and with him up to 1794 correspondence was conducted about her assignment to the city.

The low creeping arcades of both rows, which are closed quadrangles measuring 110x160 m in the Red and 122x163 m in the Flour rows and conceived by Vorotylov as two wings of a single complex, immediately set the tone not only for the development, but also for the design of the entire area. A parade ground was arranged between the rows; by the end of the 18th century. paved with cobblestones. This, on the one hand, opened both buildings for simultaneous inspection, and on the other, it seemed to include the Volga in the ensemble of the square. The planting of tall trees on the site of the parade ground took place already in the 1940s.

Contrasted with the usually uncrowded square, the galleries of the Gostiny Dvor with their smooth floor of stone slabs, ornate signboards, showcases and barkers served not only as the center of the busy trading life of the Volga city, but also as a place for walks and meetings of ordinary people. In the morning, clouds of birds, especially pigeons, flocked to the Flour Rows - each meadowsweet before the opening of the shop always brought them a scoop of grain.

In 1797, he took the post of the first Kostroma provincial architect Nikolai Ivanovich Metlin (1770-1822)... A native Muscovite, the son of an architect, who studied architecture in practice, he was still in Moscow doing some construction work, mainly in Kitai-Gorod. With the appointment to Kostroma, Metlin gained the desired independence. In 1806, under his supervision, construction began "Buildings of public places", designed to accommodate most of the provincial institutions. The construction was carried out on site and partly on the foundations of the former stone salt store, near the wall of the "New City". As usual for state-owned buildings, the "exemplary" project drawn up by A.D. Zakharov was used.

Public places before the breakdown of the square. Con. XIX - early. XX century

However, Metlin took a creative approach to this project. Firstly, he turned the building towards the square not with a facade, but with its end, and secondly, he somewhat reduced it in volume due to the tightness of the site. Nevertheless, this bold decision did not lead to the impoverishment of the square's appearance. Built in the style of classicism, the "Building of Public Places" looks very impressive even from the end: with a low basement floor, lively square windows, twice as high on the first floor, completely rusticated, and on the second floor of an even larger size.

The design of the central entrance plays a special role not only for the "Building of public places". Initially, Metlin erected a six-column portico with a pediment, raised on a stylobate, and a wide outer limestone staircase. But he did not take into account the fragility of the material - the steps were chipped, and in winter frost appeared on them. Officials and visitors began to be afraid to walk up the high and steep stairs, because more than once, slipping, they rolled head over heels down from it. In 1814, Nikolai Ivanovich proposed "an external staircase made of white stone, trodden from a lot of walking with feet, from the inconvenience of walking to sheathe boards."

Of course, this was a temporary exit, and such a staircase looked ugly. In 1832, the Nizhny Novgorod architect I. Efimov partially rebuilds the facade of the building - he moved the outer staircase inside, dismantled the old portico and made a new unconventional composition - with four Ionic columns, set in pairs on podiums cut through by arches, supporting the pediment.

Public places and Voskresenskaya Square. Con. XIX - early. XX century

Pushed far out onto the sidewalk, the portico is clearly visible from the square and serves as its decoration, at the same time it is on the same axis with the porticoes of the Red Rows facing the Volga, which includes the building of public places in a single ensemble with them.

The famous writer A.F. Pisemsky, who himself served for some time in the middle of the last century as an assessor of the provincial government located here, described the building of public places in a number of works. For example, here at the very top "in small and very dirty rooms" occupied by the Order of public charity, the hero of the story "The Old Man's Sin", accountant Iosaf Iosafych Ferapontov, lived for many years.

The building of public offices was completed and occupied by institutions in 1809. And even earlier, in September 1808, a wealthy Kostroma baker, the owner of five houses (including a two-story brick one on the square itself) Ilya Rogatkin and his father-in-law is a merchant Ivan Botnikov filed a petition for permission to build a large three-story stone house on the face of Yekaterinoslavskaya Square between Pavlovskaya (now Mira Avenue) and Yeleninskaya (Lenin) streets. In accordance with the needs of tight-fisted customers, N.I. Metlin drew up a project of a building with a facade that dispenses with a minimum of decor: the weighted first floor is, as it were, a pedestal for the two upper ones, the entablature has only basic divisions.

on Mira Ave., 1

By 1810, the house was already laid, but due to the Patriotic War of 1812, construction was delayed until 1815. In his half, facing Pavlovskaya Street, Rogatkin opened an inn, mainly for peasants who came to the bazaar in the Big flour rows. In 1834, this part of the building was acquired by second lieutenant A.A. Lopukhin, who arranged, in addition to the inn, a drinking house on the ground floor. Lopukhin's inn was notorious. In August 1841, the famous historian M.P. Pogodin, who was traveling around Russia, stayed there. He wrote in his diary that he was settled in a disgusting room, where he could not sleep for a minute, attacked by hordes of bedbugs. His whole body was swollen, he just exclaimed: "Oh, Russia!" - and was forced to "flee in a tarantass."

At the end of April 1848, the playwright A.N. Ostrovsky lived here for several days, making his first trip from Moscow to the Shchelykovo estate with his father's family. In his travel notes, he explains that they had no choice, since the best hotels in the city burned down in the September 1847 fire. Now that Ostrovsky lived in the house, albeit for a short time, is reminiscent of a memorial plaque.

At the same time, M.E. Saltykov-Shchedrin, accompanied by a gendarme officer from St. Petersburg to Vyatka exile, stayed for the night at Lopukhin's inn. the fire, about which the newspapers wrote a lot. This event, accompanied by the anecdotal actions of perplexed local administrators, found its reflection in the "History of a city" when describing the fire in Foolov.

At the end of the XIX century. Lopukhin was sold their part of the house to General Kolzakova - in pre-revolutionary times there was the Rossiya hotel, which was kept by Kostrova, and the Moulinruzh cinema, and after October - the organization of the Bolshevik party. Then the building was called the House of Communists, and from its balcony overlooking the square, prominent party and state leaders who came to Kostroma spoke to the townspeople.

The fate of the second, "Botnikovskaya" part of the house was different. It suffered quite a lot from the fire of 1847, and the half-ravaged Botnikovs sold it to A.N. Grigorov (1799-1870) in 1855, who rebuilt the house and settled in it. The description of the interior of this house has been preserved: there are 6 rooms on the ground floor, 5 in the 2 nd and 7. All rooms are heated by means of two mechanical ovens located in the lower floor, from which air-flow valves are connected to all floors. The floors are planks, painted on the 1st and 3rd floors under parquet with oil paint, and on the 2nd floor with oak parquet. A cast-iron staircase leads to the 2nd floor from the entrance, and a wooden one, painted with oil paint, with a balustrade, to the 3rd floor. The walls in the mezzanine in three rooms are decorated with marble, while the rest of the floors and in the three mezzanine rooms are covered with the best French wallpaper. " In the courtyard there was a stone building "human", a cellar, a stable, a barn, a coach shed with a hayloft and a bathhouse with a laundry.

The new owner left behind a grateful and long memory in Kostroma. Tulyak by birth, brought by the wave of 1812 to the Kostroma estate of Berezovka, which belonged to his mother, he received a good education at home, in 1821 he entered military service as a cadet in the 20th artillery brigade and was soon promoted to an officer. The brigade was stationed in Ukraine, in the city of Tulchin - the center of the Southern secret society. There Alexander Nikolayevich became close with many Decembrists, in particular with the young Count S.N. Bulgari, sharing their beliefs. However, having married and retired, he settled in the Aleksandrovskoye estate in the Kineshemsky district that he bought - the reprisal against the Decembrists bypassed him. After living for many years in the village, Grigorov moved to Kostroma, where he was elected a conscientious judge. In 1855, his wife's brother, millionaire and philanthropist P.V. Golubkov, died, leaving the Grigorovs a huge fortune, a significant part of which Alexander Nikolaevich donated to charity and public needs of Kostroma. In 1858, at his own expense, he founded and provided material support for the first female gymnasium in Russia, which was named "Grigorovskaya".

After the death of A.N. Grigorov, the house was inherited by his daughter Lyudmila, married Penskaya. Widowed early, she mainly lived in the Kineshma estate with her brother's family, while the house in Kostroma was rented out for a control ward. This institution arose in 1864, during the era of bourgeois reforms, and supervised the financial activities of banks, etc. And during the NEP, the building was occupied by the White Bear restaurant.

The land at the corner of the square with Shagova Street and Mira Avenue has long belonged to the rich noble family of the Borshchovs, who had a wooden house with a vegetable garden here (there was a “horse ground” nearby before the transfer to Pavlovskaya Square at the end of the HUNT century). Of these, the most famous was Sergei Semenovich Borshov (1754-1837). A venerable warrior of the Suvorov era, lieutenant general, in the Patriotic War of 1812, he held an important and responsible post of general-food master (chief of supply) of the Russian army. Appointed as a senator after the end of the war, Borshchov wanted by building a luxurious mansion in the very center of Kostroma, as it were, to emphasize his high official position in front of his fellow countrymen.

A rally on the square in front of the facade of the Borshchev house.

Construction began in 1819 - based on the so-called. "Exemplary project No. 10", partially modified by NI Metlin, who supervised the work. The construction of this palace-type residential building, the only one in Kostroma, was basically completed by 1822. “The large scale and representativeness determined its perception as a public building, - noted the famous art critic VN Ivanov. - He organically entered the architectural ensemble of the center. The central part of the main facade of the mansion, raised due to the mezzanine floor, is highlighted by an eight-column portico of the Corinthian order. The colonnade is placed on a pedestal and looks monumental and solemn. A cast-iron staircase leading to the second floor from the main lobby deserves attention in the interior of the mansion. The ceremonial double-height halls, which occupy part of the house, make up a suite. "

In the 1820-1830s, the owner's younger sister Natalya Semyonovna (1759-1843) visited the house more than once. An intelligent and beautiful girl, she was brought up at the Smolny Institute and in 1774 was immortalized in the poems of A.P. Sumarokov "Letter to the girls Nelidova and Borshchova", and two years later captured in the portrait of D.G. Levitsky (kept in the Russian Museum) ... After graduating in 1776 "with the code" of the institute, Borshchova lived at the royal court, being from 1809 the chamberlain over the maids of honor and the "cavalier lady". She was married twice: to K.S. Musin-Pushkin and to General Baron V. von der Hoven.

In the Russian Museum there is a pastel portrait of Borshchov's daughter Alexandra Sergeevna, married Bibikova, made by A.G. Venetsianov around 1808.

After the death of S.S. Borshchov, the house was inherited by his son Mikhail Sergeevich. He, being a chamberlain, constantly lived in the capital, but rarely visited Kostroma. In 1847, the building was badly damaged in a fire. Borshchov did not want to spend money on its restoration and in March 1849 he sold the house to the Alexander merchant A.A. Pervushin, who overhauled it and opened the best London hotel in the city. This name was often played around by local jokers. A.N. Ostrovsky in the play "Dowry" portrayed Kostroma under the name of Bryakhimov, and remade "London" into "Paris". The young and wealthy merchant Vozhevatov offers the actor Robinson, who first came to the Volga city:

Vozhevatov (quietly). Do you want to go to Paris?

Robinson. How to Paris? When?

Vozhevatov. Tonight ... How can such an artist be

Paris cannot be visited. After Paris, there will be some price for you!

Robinson. Hand!

Vozhevatov. Are you going?

Robinson. I'm going!

Later, Robinson reminds: "So you promised to go to Paris with me" - and is upset that he does not know French.

Vozhevatov. Yes, and it is not necessary at all, and no one there says

in French,

Robinson. The capital of France ...

Vozhevatov. What a capital! What are you, are you in your mind! What

Paris do you think? We have a tavern on the square, "Paris", that's where I wanted to go with

you go.

Photo by Alexander Alexandrovich Makarevsky

At the provincial fair.

In the summer of 1858, the poet N.A. Nekrasov arrived and stayed in one of the rooms of the Pervushin hotel, intending to hunt in the vicinity of Kostroma. He needed to find a hunting companion who could show the places rich in game. In the morning Nikolai Alekseevich drank tea, sitting by the window and looking at the square. He saw a man coming out of Yeleninskaya Street and heading for the market in the Big Flour Rows, hung with bundles of a dead bird. Nekrasov sent a servant for him, and he soon brought a hunter, who turned out to be a peasant from the village of Shoda, Kostroma district, Gavrila Yakovlevich Zakharov. Their long conversation continued with a feast - the hunter spent the night in Nekrasov's room, and the next day on hired troikas of horses they set off for Shoda, stopping along the way and successfully hunting game birds.

Later, Gavrila became a constant companion of Nikolai Alekseevich on his expeditions to the Kostroma forests and swamps. The sharp-witted and observant huntsman told the writer a lot about the remarkable local events, which he witnessed - one of his stories about the murder by a local forester of two similar merchants, the poet based the plot of his famous poem "Peddlers", published by him in 1861 with a dedication to "friend- to a friend. "

However, N.A. Nekrasov was not the first famous poet who lived in the "house of Borshchov". The building, the best in the city, was the residence of the crowned heads when they passed through Kostroma. In 1834 Nicholas I stayed there, in 1837 - the heir to the throne, the future Emperor Alexander II. The latter was accompanied by his tutor, poet V.A. Zhukovsky on his trip to Russia. During his short stay in Kostroma, Vasily Andreevich not only saw the local sights and got acquainted with the local writers, but also accepted and supported a prominent local historian who was persecuted by the Kostroma bishop for spending a lot of time and energy as a priest on historical and ethnographic research.

In 1865, a fire broke out in the newly built building of the city theater on Pavlovskaya Street. It was restored for two years, during which the troupe gave performances in the house of Pervushin.

After the abolition of serfdom in Russia, a number of bourgeois reforms were carried out. The most consistent of them is the judicial one, carried out in 1864. Instead of the old estate court - a citadel of bribery and chicanery - a new, public court was established with the participation of jurors. The reform was introduced in the country gradually - only in May 1871 a district court was opened in Kostroma to examine criminal and civil cases of all classes. The waiting residents of Kostroma prepared a generous gift for him - with the money collected from the population, they bought and handed over to the court the house of Pervushin.

Since the end of the last century, the District Court has been increasingly hearing cases of participants in the revolutionary movement. In this regard, in 1906, the combat squad of the Kostroma Committee of the RSDLP raided the courthouse in order to seize the investigative materials of their arrested comrades.

The building of the Kostroma District Court is reflected in Russian literature as well. For many years the hero of the famous work of AM Remizov "The Indefatigable Tambourine, or the Story of Ivan Semenovich Stratilatov", a great connoisseur and collector of "antiquity", served as a scribe in it. His prototype was a minor official of the district court and an active member of the provincial scientific archival commission, Alexander Pavlovich Poletaev, whom the writer who often visited Kostroma met at his friend I.A. Ryazanovsky, who, incidentally, also served in the judicial department.

At the end of 1917, the district court was liquidated, and the building housed many different institutions. Then it was heated by stoves - in almost every room there was a "potbelly stove" (the city was going through a fuel crisis), the pipe of which was led out through the window - in the photograph the house looked like a bristling hedgehog.

The cultural revolution caused a craze for theater in Kostroma. There was even an opera, but the ballet studio gained particular popularity among the Kostroma residents - someone wrote humorous poems ending with the words:

And everything from three to forty-two

Have gone to the ballet ...

The city authorities have already agreed to provide the building for an opera and ballet theater. However, by that time the republic had switched to the NEP rails, the principle of self-sufficiency had acquired great importance, and in a city with a population of 70 thousand, such a theater would still not have been able to exist without large subsidies. The theater had to be abandoned.

Borshchov House (1822)

One of the most beautiful buildings in the city. Poets V. Zhukovsky, N. Nekrasov and other guests of Kostroma stayed here

Next to the imposing and representative "Borshchov House", a two-storey brick house with a balcony located on the other side of Shagova Street and at its corner with the square looks especially modest. It stands on the site of the ancient Church of the Annunciation, which also stood on the current square. The church burned down in 1773 and was rebuilt in a new place, but retained a small piece of land in the ashes. The zealous archpriest of the Annunciation Church, Fyodor Ivanovich Ostrovsky, the grandfather of the great playwright, decided to put this plot of trapezoidal shape under construction and at the end of 1808 submitted a petition for the construction of a two-story building there for the residence of the clergyman. The plan of the building, skillfully overcoming the difficulties of "tying" it to an inconvenient site, was drawn up by Fyodor Ivanovich's friend A.V. Krasilnikov (see below about him).

The start of construction was postponed for a long time - back in 1810 there was a wooden bakery of the merchant O. Akatov. And only in the inventory of households in 1828 is the house of the clergyman of the Annunciation Church marked "new", that is, built two or three years ago.

At the end of the last century, the house was rented by the merchant D. Khorev, who opened the "Passage" tavern there. He also served the neighboring district court - according to the then rules, after the trial, the jurors retired to a special room and could not leave it until a guilty or acquittal verdict was passed. The debate, however, often dragged on for many hours - in such cases, the taverns from the tavern brought pots with dinner to the "recluses".

After the victory of the October Revolution, the building was occupied by the provincial extraordinary commission for combating counterrevolution and sabotage - a machine gun was then installed on the balcony. At the head of the Kostroma Gubchek were prominent party workers, professional revolutionaries Jan Kulpe, MV Zadorin and others. Gubcheka was here until the liquidation in 1922.

In the mid-1820s, the decoration of the last, northern side of the square was completed, which was associated with the estate of PI Fursov.

1903. By Henry Luke Bolley

Pyotr Ivanovich Fursov was born in 1796 in the family of a minor official of the Moscow departments of the Senate. In early childhood, he was taken to St. Petersburg and assigned to the Academy of Arts for government support. Surrounded by strangers, essentially left to himself, Fursov led a bohemian life with revelry and debauchery, fell ill with a serious illness that killed many talented Russian people. Therefore, his success at the academy, where he studied architecture, left much to be desired. In 1817, Pyotr Ivanovich was released from the Academy of Arts and returned to Moscow, where he made odd jobs or helped other architects. In 1822, having learned that after the death of N.I. Metlin in Kostroma, the position of the provincial architect was vacant, he submitted a petition and was appointed to this position.

It was here, in favorable conditions - in Kostroma, great construction work was carried out - and the outstanding talent of the architect unfolded.

Guardhouse building (1826)

Creation of the provincial architect Peter Fursov

Already in October 1823 he drew up a draft of the guardhouse, the construction of which was completed in 1826. Since the Middle Ages, a strong garrison has traditionally been located in the city - first archers, gunners and squeakers, then, in the 18th century, the Old Ingermanland musketeer regiment, etc. The riot and revelry of officers were considered at that time in the order of things, therefore the city society maintained a guardhouse. The wooden guardhouse was originally located on the banks of the Volga, near the Moscow outpost. It fell into disrepair, and Fursov decided to move it to the square (that was a bold idea, since they tried not to keep buildings of this purpose "in sight", but so that it would serve as an adornment of the city center). Previously, in its place was the apple orchard of the factory owners Volkov.

Despite its small size, the building is inherent in monumentality. The emphasis is placed on the six-column portico of a strict Doric order against the background of a deep semicircular niche - exedra, which achieves plasticity and a cut-off effect.

The architect himself was satisfied with his creation and in May 1826 reported that "it was built in all parts in the best way ... to the plan, facade and profile correctly composed for this." At the same time, he pointed out that "to decorate the square and the newly constructed building, it is necessary ... to arrange a fence at the sharp corners entering the square, through which the building will receive a connection with other structures and ... this polygon will receive a proper picture." Indeed, a lattice wooden fence was soon erected.

Two lanterns were installed in front of the guardhouse and a bell was hung to call the guard “in a gun”. At the beginning of March 1917, the last Kostroma governor I.V. Khozikov, the police chief, and others were kept here, and during the years of the civil war - the prisoners of Kolchak's officers.

The guardhouse especially benefits from the neighborhood with another wonderful creation of P.I. Fursov - a fire tower.

Bored wooden Kostroma - in 1904, 84% of all houses in the city were wooden, and 53% with wooden (boards, shingles) roofs - more than once suffered from devastating fires, as the chronicles tell about and archival documents testify. A terrible fire in May 1773 destroyed essentially the entire city. To fight fire back in the 18th century. a fire station was established and wooden watchtowers were built, but the latter sometimes caught fire themselves. Therefore, in the order of the governor it was announced: "A decent watchtower does not interfere here, which together would serve as a decoration for the city and protect every inhabitant with safety during fire accidents."

Fursov made the designs of the watchtower and the guardhouse almost simultaneously, and the construction contract stipulated that all work should be carried out "according to the given plan and facade without the slightest deviation ... according to the testimony of the provincial architect."

The tower is designed in the form of an antique temple with an almost cubic volume with a six-column portico. Above the cornice of the main building, an attic floor was erected, as it were, softening the transition to an octagonal sentinel pillar, narrowing upward. The total height of the tower is 35 meters. Its architectural solution not only corresponded to the functional tasks of the building, but also helped to organically include the watchtower in the composition of the square ensemble as an expressive vertical, contrasting with the creeping arcades of the rows.

The writer A.F. Pisemsky, who personally knew the architect, formulated the impression that the buildings of P.I. Fursov make. In the novel "People of the Forties", "a gifted architect, still academic education, a drunkard, a beggar, not loved either by the authorities or by the public, is brought out." After him, there are still two or three buildings left in the provincial town, in which you immediately noticed something special, and you were doing well, as usually happens when you stop, for example, in front of Rastrelli's buildings. "

Kostromich's creations had a peculiar effect even on such people insensitive to art as Nicholas I. In his memoirs "From the Past", the famous publicist N.P. , and then said: “I don’t have one in St. Petersburg”.

Fire tower (1827)

The brainchild of the architect Pyotr Fursov

Some of the fire brigade employees also lived in the tower. In 1874, Vasily Nikolayevich Sokolov was born here in the family of a firefighter - an active participant in the revolutionary movement, a member of the All-Union Communist Party of Bolsheviks since 1898, an agent of Iskra, a prominent party and Soviet worker. In the book "Party ticket No. 0046340" he told interestingly about his childhood in Kostroma.

With the completion of the construction of the guardhouse and watchtower in 1826, the design of the central square along the perimeter was completed - all this took about forty years. Even then, she aroused admiring reviews from contemporaries. So, PP Sumarokov in his book "Walks in 12 provinces with historical and statistical notes in 1838" wrote: "Kostroma ... is located on a smooth plain, near the Volga. The buildings are specious, and all the streets have good pavements, great neatness. The mentioned square is surrounded by stone houses, benches, a tower with a pediment, columns, light architecture, occupies one of its sides, and in the middle there is a wooden, temporarily, monument with the inscription: "Susanin Square". This square looks like a loose fan, 9 streets adjoin it, and at one point you can see all of their lengths. There are few such pleasant, cheerful-looking cities in Russia. Kostroma is like a smartly finished toy. "

Monument to Tsar Mikhail Fedorich and citizen Ivan Susanin. Photo of 1875-1878

However, in the 1830s, the appearance of the square was not yet fully formed - it looked too deserted. There was a lack of some kind of structure that would unite into a single ensemble all eight buildings semi-encircling the area. A monument to Ivan Susanin turned out to be such a necessary structure.

For the first time, the idea of perpetuating the historical feat of the Kostroma peasant, who at the beginning of 1613 led a detachment of enemies into the impenetrable jungle, sacrificing his life in the name of saving his homeland, was put forward by a local teacher and writer Yuri Nikitich Bartenev, a good friend of A.S. Pushkin and N.V. Gogol. During the arrival of Nicholas I, it was possible to obtain his consent to erect a monument to the national hero, in commemoration of which, by a decree of June 8, 1835, Yekaterinoslavskaya Square was renamed into Susaninskaya.

The creation of the monument was entrusted to the gifted sculptor Vasily Ivanovich Demut-Malinovsky, who became famous for his work on the decoration of the arch of the General Staff Building in St. Petersburg. On August 7, 1841, the laying of the monument took place, delivered from the capital in September 1843. The death of the sculptor in 1846 slowed down the progress of work, and the monument was unveiled in a solemn atmosphere only on March 14, 1851. It was a round granite column, placed on a quadrangular granite pedestal, lined on the sides with metal boards, with a relief image of the scene of the hero's death on one of them. At the top of the column is a bronze bust of the young Tsar Mikhail wearing the "Monomakh cap"; at the foot, on a pedestal, is the expressive kneeling figure of Ivan Susanin. The monument weighed 17 thousand poods and was 7 fathoms high.

The monument, facing the Volga and surrounded by a low cast-iron lattice of artistic casting with lampposts in the corners, seemed to "pull together" the space of Susaninskaya Square, paved in 1843 with small cobblestones, and perfectly fit into its ensemble. However, the symbolism of this monument with the kneeling sacrificial pose of the old peasant was alien and unacceptable for the advanced circles of Russia and the broad masses: their ideal of embodying the image of an unyielding patriot was expressed in the poem "Who Lives Well in Russia" by N.A. Nekrasov:

Savely, in the words of the poet, is a "bogatyr of the Holy Russian", a rebel peasant. Since after the October Revolution the idea embodied in the monument turned out to be inconsistent with the new era, it was demolished.

At the end of the XIX century. parade grounds began to give way to squares. This trend also touched Kostroma. On June 11, 1897, the City Duma decided: "To destroy Susaninskaya Square and build a square in its place, according to the plan presented, so that the monument to Susanin would be at the beginning of the square and a sufficient width of the street would pass around the square." Susaninsky square*, occupying a plot of 3.5 thousand square meters. m., originally had a semi-oval shape, it was crossed by eight paths converging in the center. 556 acacia bushes and 1902 spyria bushes were planted in the park - they were periodically cut low (trees appeared here already in the 1930s). The square was surrounded by a beautiful metal fence 80 cm high.

On October 19, 1905, young people, mainly students, gathered in Susaninsky Square, since the just promulgated tsarist manifesto declared freedom of meetings. Bolshevik orators addressed the audience. However, the police spread rumors among local traders and peasants who had gathered with goods (it was a market day) that the protesters intended to destroy the monument to Susanin, and then smash the shops and the market. An excited dark crowd with shafts, chains, etc. began to flock to the square. The rally had to be interrupted, and its participants in a column moved to Tsarevskaya Street. There they were attacked by their pursuers and perpetrated savage reprisals.

After February 1917, the meetings in the park resumed. Therefore, on the eve of the first anniversary of October, Susaninskaya Square was renamed into Revolution Square.

Russia, Kostroma,

Address: Russia, Kostroma

Start of construction: 1781 year

Completion of construction: 1784 year

Coordinates: 57 ° 46′4.4 ″ N 40 ° 55′37.5 ″ E

Architect: Karl von Claire

The central square of the city is interesting in that it has preserved an integral architectural ensemble, consisting of buildings built at the beginning of the 19th century. Borshchev's house, fire tower, guardhouse and public places perfectly fit into the spatial perspective and perfectly harmonize with each other. In addition, the main square of Kostroma is a favorite place for walks for city residents and tourists who come here.

View of Susaninskaya Square from Sverdlova Street

How Susaninskaya Square was created

The history of the square, named after the Kostroma peasant, has more than 230 years. It began to be built after the adoption of the general urban planning plan in the city - in the 80s of the 18th century. It was during the reign of Empress Catherine II, and it is not surprising that the new Kostroma Square was immediately named Catherine Square.

According to the original plan, the area was supposed to be made semicircular, but later it acquired the shape of a polyhedron. In 1823 the square was covered with cobblestones. And in 1835, by the decision of Emperor Nicholas I, it was renamed into Susaninskaya. Today this part of the city consists of a large public garden located in front of Gostiny Dvor, and the square itself, from which the streets radiate out like rays throughout the city.

Fire Tower

City architect Pyotr Ivanovich Fursov became the author of the tallest building in the central square of Kostroma - the fire tower. Today it is rightfully considered one of the city's visiting cards.

Fire tower on Susaninskaya square

The tower was built in the style of mature classicism in the late 1820s. According to the plan of the then governor K.I. Baumgarten needed a tall building both to decorate the main square and to alert residents in the event of a fire. The two-story base of the watchtower turned out to be so spacious that all the necessary units of the city fire service were freely located in it.

At the top of the tower, as if "growing" from the main building, a beautiful lantern with a balcony was erected. When, in the middle of 1830, Emperor Nicholas I, who was passing through Kostroma, publicly expressed his admiration for the tower, it was considered the best in the Russian province. Almost all the time the building of the fire tower was used for its intended purpose. And only recently it was transferred to the city museum, and there are expositions that tell about the history of firefighting in Russia.

Guardhouse on Susaninskaya Square

Guardhouse

On the right side of the watchtower there is an unusual building, which in previous years housed a guardhouse. It was erected in the mid-1820s to replace a dilapidated wooden structure. Kostroma Architect P.I. Fursov, a recognized master of the Empire style, created the building extremely magnificent for the places of detention of the guilty. True, it was not ordinary soldiers who served their sentences here, but only noble officers. Therefore, the deliberate solemnity of the facades of the "military prison" turned out to be quite appropriate.

Today, the guardhouse building is given to the city museum, and military-historical collections are exhibited in its halls. Here you can see rare exhibits from the 12th century to the present day: ancient weapons, ammunition, maps of military campaigns and personal belongings of soldiers.

Borshchov's mansion

Perhaps the most representative building overlooking Susaninskaya Square is a large classical mansion, which is more like a palace in its dimensions. It is called Borshchev's house.

Borshchov's mansion on Susaninskaya square

The exact date of the construction of the mansion has not been preserved. Some historians say that it was erected in 1824, others claim that it happened 6 years later. The architect who prepared the project of the building is also unknown. It could have been N.I. Metlin, and P.I. Fursov.

The owner of the mansion was the famous Kostroma, Senator and Lieutenant General Sergei Semenovich Borshchov. He came from a noble family of nobles who served at the royal court for several centuries. In 1817, Borshchov resigned and decided to build a stone house for himself instead of the old mansion. Construction began in 1819 with the first wing. And then they built the whole large building as a whole.

The facade of the central part of the magnificent mansion is decorated with eight austere columns and a portico. And its side parts have two floors. Among the famous guests, Tsar Nicholas I and the future Emperor Alexander II visited the house. Poets also came here - Vasily Andreevich Zhukovsky and Nikolai Alekseevich Nekrasov.

Public places on Susaninskaya Square

Official places

For a long time, the city did not have a separate place to house the provincial authorities. Due to frequent fires, the administrative services found shelter either within the walls of the Epiphany Monastery or in the Trading Rows. And finally, at the beginning of the 19th century in the center of Kostroma, a special building of Public Places was built, the project of which was carried out by the provincial architect Nikolai Ivanovich Metlin.

The facade of the house, built in the style of classicism, is decorated with four columns and a strict Ionic order. And the portico on which they stand is so high that arched openings were made under it especially for pedestrians. Initially, a wide white-stone staircase led to the square from the building. But during the reconstruction, which was carried out in the 1830s, this staircase was removed. Today, the offices continue to be used for their intended purpose - they are occupied by the services of the city mayor's office.

Monument to Ivan Susanin on Susaninskaya Square

Monument to Ivan Susanin

The very first monument to the savior of the Russian Tsar Mikhail Fedorovich was erected in the city by order of the Russian Tsar Nicholas I. In 1851 it was created by the talented sculptor Vasily Ivanovich Demut-Malinovsky. The majestic monument, located on a high column, depicted the young king. And at the foot of the monument, a peasant was kneeling, who did not spare his life for the sovereign. At the very beginning of the 20th century, the Kostroma authorities laid out a beautiful park in front of this monument.

In 1918, the young Soviet state approved its own ideology and adopted a decree on the demolition of monuments associated with the tsar and his servants. This document became the basis for the decision of the Kostroma authorities, and the old monument was dismantled.

The monument that can be seen on the square today was erected in 1967. The 12-meter tall figure of Susanin, facing the Volga, was made by the Moscow sculptor-monumentalist Nikita Antonovich Lavinsky.

Zero Meridian on Susaninskaya Square

How to get there

The square is located in the historical center of the city, on the left bank of the Volga.

By car. The road from the capital to Kostroma takes 4.5-5 hours (346 km) and runs along the Yaroslavl highway and the M8 highway (Kholmogory). In Kostroma, cross the road bridge to the left bank of the Volga and turn left to st. Soviet, along which you can get to the square.

By train or bus. From the Yaroslavsky railway station to

Susaninskaya Square is the historical center of Kostroma. Its appearance was formed at the end of the 18th century, when Empress Catherine II approved a new "fan-shaped" layout of the city. The buildings of the square, which have survived to this day, date back to the 18-19 centuries.

Susaninskaya Square was initially called Yekaterinoslavskaya, in honor of Catherine, who made a significant contribution to the development of the city. In 1835, Nicholas I renamed it Susaninskaya in honor of Ivan Susanin.

Ivan Susanin is a national hero of the Time of Troubles, when Russia was under the rule of self-proclaimed tsars, supported by Polish troops. He was born in the village of Domnino, Kostroma district, which was the ancestral domain of the Romanov family (the future tsarist dynasty of Russia).

After being elected to the throne, Mikhail Romanov lived for some time with his mother, nun Martha, in the village of Domnino, and it was at this time that a Polish armed detachment appeared in its vicinity, which came to Russia to kill Mikhail Romanov, so that the Polish prince Vladislav could again fight for the royal throne.

The Poles came across Ivan Susanin, who for a fee agreed to take them to the village of Domnino. He managed to send his son-in-law to Michael with the advice to take refuge again in the Ipatiev Monastery, and he himself led them into the forest. The Poles quickly realized that they were being taken in the wrong place. They killed Susanin, but they could no longer kill Mikhail Romanov.

Even under the tsar, a monument to Ivan Susanin was erected here on the square, which was demolished in 1918. New monument “Ivan Susanin. Patriot of the Russian Land ”was erected in 1967. It was installed not on Susaninskaya Square, but slightly lower on the descent to the Volga Embankment, among the shopping malls.

The most recognizable building on Susaninskaya Square, and even, in a sense, a symbol of Kostroma, is the Fire Tower. It was built in 1768, that is, in fact, it became one of the first buildings on the square after its reconstruction.

On the square, you must also visit the Shopping Rows. They have completely preserved the appearance of the 19th century and, in fact, have become a city landmark, and not a place of trade.