What animal was revered in the Minoan civilization. Minoan civilization of Crete

Prerequisites for the formation of states in Crete

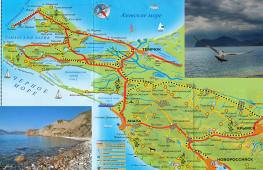

Crete was the oldest center of civilization in Europe. According to its geographical position, this mountainous island, elongated in length, closing the entrance to the Aegean Sea from the south, represents, as it were, a natural outpost of the European continent, extended far south towards the African and Asian coasts of the Mediterranean Sea. Already in ancient times, sea routes crossed here, connecting the Balkan Peninsula and the Aegean Islands with Asia Minor, Syria and North Africa. The culture of Crete, which arose at one of the busiest crossroads of the ancient Mediterranean, was influenced by such heterogeneous and widely separated cultures as the ancient "river" civilizations of the Middle East (and), on the one hand, and the early agricultural cultures, the Danubian lowland and Balkan Greece, on the other hand. another. But a particularly important role in the formation of the Cretan civilization was played by the culture of the Cyclades archipelago neighboring Crete, rightfully considered one of the leading cultures of the Aegean world in the 3rd millennium BC.

The time of the emergence of the Minoan civilization is the turn of the III-II millennium BC. or the end of the Early Bronze Age. Until that moment, the Cretan culture did not stand out in any noticeable way against the general background of the most ancient cultures of the Aegean world. The era, just like the era of the Early Bronze Age that replaced it (VI-III millennium BC), was in the history of Crete a time of gradual, relatively calm accumulation of forces before a decisive leap to a new stage of social development. What prepared this leap? First of all, the development and improvement of the productive forces of the Cretan society. Even at the beginning of the III millennium BC. in Crete, the production of copper was mastered, and then bronze. Bronze tools and weapons are gradually replacing similar stone products. Important changes take place during this period in the agriculture of Crete. Its basis is now becoming a new multicultural type of agriculture, focused on the simultaneous cultivation of three main crops (the so-called "Mediterranean triad"), namely -

- cereals (mainly barley),

- grapes,

- olives.

Growth in productivity and population

The result of all these economic shifts was an increase in the productivity of agricultural labor and an increase in the mass of surplus product. On this basis, reserve funds of agricultural products began to be created in individual communities, which not only covered the shortage of food in lean years, but also provided food for people who were not directly involved in agricultural production, for example, artisans. Thus, for the first time, it became possible to separate craft from agriculture, and the development of professional specialization in various branches of handicraft production. The high level of professional craftsmanship achieved by Minoan artisans as early as the second half of the 3rd millennium BC is evidenced by finds of jewelry, vessels carved from stone, and carved seals dating back to that time. At the end of the same period, the potter's wheel became known in Crete, which made it possible to achieve great progress in the production of ceramics.

Palicastro, 16th century BC. Sea style.

At the same time, a certain part of the community reserve funds could be used for intercommunal and intertribal exchange. The development of trade in Crete, as well as in the Aegean in general, was closely connected with the development of navigation. It is no coincidence that almost all the Cretan settlements known to us now were located either directly on the sea coast, or somewhere not far from it. Having mastered the art of navigation, the inhabitants of Crete already in the III millennium BC. entered into close contacts with the population of the islands of the Cyclades archipelago, penetrated the coastal regions of mainland Greece and Asia Minor, reached Syria and Egypt. Like other maritime peoples of antiquity, the Cretans willingly combined trade and fishing with piracy.

The progress of the Cretan economy during the Early Bronze Age contributed to the rapid growth of population in the most fertile areas of the island. This is evidenced by the emergence of many new settlements, which accelerated especially at the end of the 3rd - beginning of the 2nd millennium BC. Most of them were located in eastern Crete and in the vast central plain of Messara. At the same time, an intensive process of social stratification of the Cretan society is going on. Within individual communities, an influential stratum of the nobility stands out. It consists mainly of tribal leaders and priests. All these people were exempted from direct participation in productive activities and occupied a privileged position in comparison with the mass of ordinary community members. At the other pole of the same social system, slaves appear, mainly from among the captured foreigners.

In the same period, new forms of political relations began to take shape in Crete. Stronger and more populous communities subjugate their less powerful neighbors, make them pay tribute and impose all sorts of other duties. Already existing tribes and tribal unions are internally consolidated, acquiring a clearer political organization. The logical result of all these processes was the formation at the turn of the 3rd-2nd thousand of the first "palace" states, which took place almost simultaneously in various regions of Crete.

The first class societies and states

Palace style pithos. Knossos, 1450 BC

Already at the beginning of the II millennium BC. several independent states have developed on the island. Each of them included several dozens of small communal settlements, grouped around one of the four large palaces now known to archaeologists. This number includes the palaces of Knossos, Phaistos, Mallia in the central part of Crete and the palace of Kato Zakro on the east coast of the island. Unfortunately, only a few survived from the "old palaces" that existed in these places. The later building almost everywhere erased their traces. Only in Phaistos, the large western courtyard of the old palace and part of the interior adjoining it have been preserved.

Among the palace utensils of this period, clay painted vases of the Kamares style are of the greatest interest (their first examples were found in the Kamares cave near Phaistos, whence the name comes from). The stylized floral ornament decorating the walls of these vessels creates the impression of a non-stop movement of geometric figures combined with each other: spirals, disks, rosettes, etc. Here, for the first time, that dynamism (a sense of movement) that will later become a hallmark of all Minoan art makes itself felt . The color richness of these paintings is also striking.

Vessel "Kamares". Palais Festus, 1850-1700 BC.

Already in the period of the "old palaces" the socio-economic and political development of Cretan society had advanced so far that it gave rise to an urgent need for writing, without which none of the early civilizations known to us can do. The pictographic writing that arose at the beginning of this period (it is known mainly from short - of two or three characters - inscriptions on seals) gradually gave way to a more advanced system of syllabic writing - the so-called linear A. Dedicatory inscriptions made in Linear A have survived, as well as, albeit in a small number, business accounting documents.

Rise of the Cretan Civilization. Predominance of Knossos

Around 1700 BC the palaces of Knossos, Phaistos, Mallia and Kato Zakro were destroyed, apparently as a result of a strong earthquake, accompanied by a large fire. This catastrophe, however, only briefly suspended the development of Cretan culture. Soon, new buildings of the same type were built on the site of the destroyed palaces, basically, apparently, retaining the layout of their predecessors, although surpassing them in their monumentality and magnificence of architectural decoration. Thus, a new stage began in the history of Minoan Crete, known in science as the "period of new palaces" or the late Minoan period.

Knossos palace

The most remarkable architectural structure of this period is the palace of Minos discovered by A. Evans at Knossos. The extensive material collected by archaeologists during excavations in this palace allows us to get an idea of what the Minoan civilization was like at its peak. The Greeks called the palace of Minos "the labyrinth" (the word itself, apparently, was borrowed by them from the language of the pre-Greek population of Crete). In Greek myths, the labyrinth was described as a huge building with many rooms and corridors. A person who got into the labyrinth could no longer get out without outside help and inevitably died: in the depths of the palace lived the bloodthirsty Minotaur - a monster with a human body and a bull's head. The tribes and peoples subject to Minos were obliged to amuse the terrible beast with human sacrifices every year, until he was killed by the famous Athenian hero Theseus. Evans' excavations showed that the stories of the Greeks about the labyrinth had a certain basis. In Knossos, indeed, a building of outstanding size or even a whole complex of buildings with a total area of 10,000 m2 was discovered, which included about three hundred rooms of the most diverse purposes.

Modern view of the Palace of Knossos. Construction ca. 1700 BC

The architecture of the Cretan palaces is unusual, original and unlike anything else. It has nothing in common with the ponderous monumentality of Egyptian and Assyro-Babylonian buildings. At the same time, it is far from the harmonic balance of the classical Greek temple with its strictly mathematically adjusted proportions. The interior layout of the palace is extremely complex, even intricate. Living rooms, utility rooms, corridors connecting them, courtyards and light wells are located, at first glance, without any visible system and clear plan, forming some kind of anthill or coral colony. Despite the chaos of the palace construction, it is still perceived as a single architectural ensemble. In many ways, this is facilitated by the large rectangular courtyard occupying the central part of the palace, with which all the main premises that were part of this huge complex were connected in one way or another. The courtyard was paved with large gypsum slabs and, apparently, was used not for household needs, but for some kind of religious purposes.

During its centuries-old history, the Palace of Knossos has been rebuilt several times. Its individual parts and the entire building as a whole probably had to be restored after each strong earthquake, which occurs in Crete about once every fifty years. At the same time, new premises were attached to the old, already existing ones. Rooms and pantries seemed to be strung one to the other, forming long rows-enfilades. Separate buildings and groups of buildings gradually merged into a single residential area, grouped around the central courtyard. Despite the well-known unsystematic internal development, the palace was abundantly supplied with everything necessary to ensure that the life of its inhabitants was calm and comfortable. The builders of the palace took care of such important comfort elements as plumbing and sewerage. During the excavations, stone gutters were found, through which sewage was removed outside the palace. A water supply system was also discovered, thanks to which the inhabitants of the palace never suffered from a lack of drinking water. The Palace of Knossos also had a well-thought-out ventilation and lighting system. The entire thickness of the building was cut from top to bottom with special light wells, through which sunlight and air entered the lower floors of the palace. Large windows and open verandas served the same purpose.

A significant part of the lower, basement floor of the palace was occupied by pantries for storing food: wine, olive oil and other products.

Gold Cup #2 from Vafio. 15th century BC.

During the excavations of the Palace of Knossos, archaeologists have unearthed a wide variety of works of art and artistic crafts. Among them are magnificent painted vases decorated with images of octopuses and other marine animals, sacred stone vessels (the so-called rhytons) in the form of a bull's head, wonderful faience figurines depicting people and animals with unusual credibility and expressiveness for that time, jewelry of the finest workmanship. , including gold rings and carved gemstone seals. Many of these things were created in the palace itself, in special workshops in which jewelers, potters, vase painters and artisans of other professions worked, serving the king and the nobility surrounding him with their work (the premises of the workshops were found in many places on the territory of the palace). Of particular interest is the wall painting that adorned the inner chambers, corridors and porticos of the palace. Some of these frescoes depicted scenes from the life of nature: plants, birds, marine animals. Others showed the inhabitants of the palace itself: slender, tanned men with long black hair styled in whimsically curly curls, with a thin “aspen” waist and broad shoulders, and “ladies” in huge bell-shaped skirts with many frills and tight corsages. Two main features distinguish the frescoes of the Palace of Knossos from other works of the same genre found elsewhere, for example in Egypt:

- firstly, the high coloristic skill of the artists who created them, their keen sense of color, and,

- secondly, art in conveying the movement of people and animals.

Bull Games. Fresco from the Palace of Knossos.

An example of the dynamic expression that distinguishes the works of Minoan painters is the magnificent frescoes, which represent the so-called "games with bulls" or the Minoan tauromachy. We see on them a rapidly rushing bull and an acrobat doing a series of intricate jumps right on his horns and on his back. In front of and behind the bull, the artist depicted the figures of two girls in loincloths, obviously the "assistant" of the acrobat. Apparently, it was an important religious ritual associated with one of the main Minoan cults - the cult of the bull god.

Scenes of tauromachy are perhaps the only disturbing note in Minoan art, which is generally distinguished by serenity and cheerfulness. He is completely alien to the cruel bloody scenes of war and hunting, so popular in contemporary art in the countries of the Middle East and mainland Greece. Yes, this is not surprising. From the hostile outside world, Crete was reliably protected by the waves of the Mediterranean Sea washing it. In those days, there was not a single significant maritime power in the immediate vicinity of the island, and its inhabitants could feel safe. This is the only way to explain the paradoxical fact that amazed archaeologists: all the Cretan palaces, including Knossos, remained unfortified throughout almost their entire history.

Religious beliefs of the ancient Cretans

In the works of palace art, the life of the Minoan society is presented in a somewhat embellished form. In fact, it also had its dark sides. The nature of the island was not always favorable to its inhabitants. As already noted, earthquakes constantly occurred in Crete, often reaching destructive force. To this should be added the frequent sea storms in these places, accompanied by thunderstorms and heavy rains, dry years, periodically bringing down on Crete, as well as on the rest of Greece, famine and epidemics. In order to protect themselves from all these terrible natural disasters, the inhabitants of Crete turned to their many gods and goddesses for help.

Goddess with snakes from the Palace of Knossos. OK. 1600-1500 BC.

The central figure of the Minoan pantheon was the great goddess - the "mistress" (this is how her inscriptions found in Knossos and in some other places are called). In the works of Cretan art (mainly in small plastic: figurines and seals), the goddess appears before us in her various incarnations. Sometimes we see her as a formidable mistress of wild animals, the mistress of mountains and forests with all their inhabitants (cf. the Greek Artemis), sometimes a blessed patroness of vegetation, primarily cereals and fruit trees (cf. the Greek Demeter), sometimes the sinister queen of the underworld, holding writhing snakes in her hands (this is depicted by her famous faience statuette of the “goddess with snakes” from the Palace of Knossos, cf. the Greek Persephone with her). Behind all these images, the features of the ancient deity of fertility are guessed - the great mother of all people, animals and plants, the veneration of which was widespread in all countries of the Mediterranean since the Neolithic era.

Next to the great goddess - the personification of femininity and motherhood, a symbol of the eternal renewal of nature, there was in the Minoan pantheon a deity of a completely different plan, embodying the wild destructive forces of nature - the formidable element of an earthquake, the power of a raging sea. These terrifying phenomena were transformed in the minds of the Minoans into the image of a mighty and ferocious bull-god. On some Minoan seals, the divine bull is depicted as a fantastic creature - a man with a bull's head, which immediately reminds us of the later Greek myth of the Minotaur. According to the myth, the Minotaur was born from the unnatural connection of Queen Pasiphaia, the wife of Minos, with a monstrous bull, which was presented to Minos by Poseidon, the lord of the sea (according to one version of the myth, Poseidon himself reincarnated as a bull). In ancient times, it was Poseidon who was considered the culprit of earthquakes: with the blows of his trident, he set the sea and land in motion (hence his usual epithet "earthshaker"). Probably, the same kind of ideas were associated among the most ancient inhabitants of Crete with their bull-god. In order to pacify the formidable deity and calm the angry elements, plentiful sacrifices were made to him, apparently including human ones (an echo of this barbaric rite was again preserved in the myth of the Minotaur). Probably, the already mentioned games with the bull served the same purpose - to prevent or stop the earthquake. The symbols of the divine bull - the conventional image of bull horns - are found in almost every Minoan sanctuary.

A young man among the lilies, "Priest-King". Fresco-painted relief, height 2.2 m. Knossos, 1600 BC.

Religion played a huge role in the life of the Minoan society, leaving its mark on all spheres of its spiritual and practical activities. This shows an important difference between the Cretan culture and the later one, for which such a close interweaving of "divine and human" was no longer characteristic. During the excavations of the Palace of Knossos, a huge amount of all kinds of cult utensils was found, including

- figurines of the great goddess,

- sacred symbols like the already mentioned bull horns,

- double ax - labrys,

- altars and tables for sacrifices,

- various vessels for libations.

Many of the premises of the palace were clearly not intended for household needs or for housing, but were used as sanctuaries for religious rites and ceremonies. Among them are crypts - caches in which sacrifices were made to underground gods, pools for ritual ablutions, small home chapels, etc. The very architecture of the palace, the paintings that adorned its walls, and other works of art were thoroughly permeated with complex religious symbols. In essence, the palace was nothing more than a huge sanctuary, a palace-temple, in which all the inhabitants, including the king himself, performed various priestly duties, participating in the rites, the images of which we see on the palace frescoes. So, it can be assumed that the king - the ruler of Knossos - was at the same time the high priest of the god-king, while the queen - his wife - occupied a corresponding position among the priestesses of the great goddess - "mistress".

royal power

According to many scientists, in Crete there was a special form of royal power, known in science under the name of "theocracy" (one of the varieties of the monarchy, in which secular and spiritual power belongs to the same person). The person of the king was considered "sacred and inviolable." Even the sight of him was forbidden to "mere mortals." This can explain the rather strange, at first glance, circumstance that among the works of Minoan art there is not a single one that could be confidently recognized as an image of a royal person. The whole life of the king and his household was strictly regulated and raised to the level of a religious ritual. The kings of Knossos did not just live and rule. They were sacred.

The “Holy of Holies” of the Palace of Knossos, the place where the king-priest “condescended” to communicate with his subjects, made sacrifices to the gods and at the same time decided state affairs, is his throne room. Before getting into it, visitors were led through the vestibule, in which there was a large porphyry bowl for ritual ablutions: in order to appear before the "royal eyes", it was necessary to first wash off all evil from oneself. Along the walls of the hall there were benches lined with knocks, on which the royal advisers, high priests and dignitaries of Knossos sat. The walls of the throne room are painted with colorful frescoes depicting griffins - fantastic monsters with a bird's head on a lion's body. Griffins lie in solemn frozen poses on both sides of the throne, as if protecting the lord of Crete from all sorts of troubles and hardships.

Socio-economic relations

The magnificent palaces of the Cretan kings, the riches stored in their cellars and pantries, the atmosphere of comfort and abundance in which the kings themselves and their entourage lived - all this was created by the labor of many thousands of nameless peasants and artisans, about whose life little is known.

Steatite vessel from Agia Triade. OK. 1550-1500 BC.

The court masters who created all the most remarkable masterpieces of Minoan art, apparently, had little interest in the life of the common people and therefore did not reflect it in their work. As an exception, we can refer to a small steatite vessel found during excavations of the royal villa in Agia Triada near Phaistos. The skillfully executed relief decorating the upper part of the vessel depicts a procession of peasants armed with long forked sticks (with the help of such tools the Cretan peasants probably knocked ripe olives from the trees). Some of the participants in the procession sing. The procession is led by a priest, dressed in a wide scaly cloak. Apparently, the artist who created this little masterpiece of Minoan sculpture wanted to capture the harvest festival or some other similar ceremony.

Some idea of the life of the lower strata of Cretan society is provided by materials from mass graves and rural sanctuaries. Such sanctuaries were usually located somewhere in the remote corners of the mountains: in caves and on the tops of mountains. During excavations, uncomplicated initiatory gifts are found in them in the form of figures of people and animals roughly molded from clay. These things, as well as the primitive inventory of ordinary burials, testify to the low standard of living of the Minoan village, to the backwardness of its culture in comparison with the refined culture of palaces.

The bulk of the working population of Crete lived in small towns and villages scattered over the fields and hills in the vicinity of the palaces. These villages, with their wretched adobe houses, closely pressed against each other, with their crooked narrow streets, make up a striking contrast with the monumental architecture of the palaces, the luxury of their interior decoration.

Rock crystal rhyton. Palace of Kato Zakro. OK. 1700-1450 BC.

A typical example of an ordinary Minoan settlement is Gournia, located in the northeastern part of Crete. Its area is very small - only 1.5 hectares (this is only slightly more than the area occupied by the Knossos Palace without buildings adjacent to it). The entire settlement consisted of several dozen houses, built very compactly and grouped into separate blocks or quarters, inside which the houses stood close to each other. The houses themselves are small - no more than 50 m2 each. Their design is extremely primitive. The lower part of the walls is made of stones fastened with clay, the upper part is made of unbaked bricks. The frames of windows and doors were made of wood. Utility rooms were found in some houses: pantries with pithoi for storing supplies, presses for squeezing grapes and olive oil. During the excavations, quite a lot of various tools made of copper and bronze were found.

There were several craft workshops in Gournia, the products of which were most likely designed for local consumption, among them a smithy and a pottery workshop. The proximity of the sea suggests that the inhabitants of Gournia combined agriculture with trade and fishing. The central part of the settlement was occupied by a building vaguely reminiscent of the Cretan palaces in its layout, but much inferior to them in size and in the richness of the interior decoration. It was probably the home of the local ruler, who, like the entire population of Gurnia, was dependent on the king of Knossos or some other lord from large palaces. An open area was arranged near the ruler's house, which could be used as a place for meetings and all kinds of religious ceremonies or performances. Like all other large and small settlements of the Minoan era, Gournia did not have any fortifications and was open to attack both from the sea and from land. Such was the appearance of the Minoan village, as far as it can now be imagined from the data of archaeological excavations.

What connected the palaces with their rural areas? We have every reason to believe that relations of domination and subordination, characteristic of any early class society, have already developed in Cretan society. It can be assumed that the agricultural population of the Kingdom of Knossos, like any of the states of Crete, was subject to duties both in kind and labor in favor of the palace. It was obliged to deliver cattle, grain, oil, wine and other products to the palace. All these receipts were recorded by the palace scribes on clay tablets, and then they were handed over to the palace storerooms, where huge stocks of food and other material values accumulated in this way. The palace itself was built and rebuilt by the hands of the same peasants and slaves, roads and irrigation canals were laid.

Labrys is a votive golden ax from the cave of Arkalochori. 1650-1600 BC.

It is unlikely that they did all this only under duress. The palace was the main sanctuary of the entire state, and elementary piety demanded from the villager that he honor the gods who lived in it with gifts, giving surpluses of his economic reserves to arrange festivities and sacrifices, however, between the people and their gods stood a whole army of intermediaries - a staff of professional priests serving the sanctuary led by a "sacred king". In essence, it was an already established, clearly defined stratum of hereditary priestly nobility, opposed to the rest of society as a closed aristocratic class. Uncontrollably disposing of the reserves stored in the palace warehouses, the priests could use the lion's share of these wealth for their own needs. Nevertheless, the people unlimitedly trusted these people, since "God's grace" lay on them.

Of course, along with religious motives, the concentration of the surplus product of agricultural labor in the hands of the palace elite was also dictated by purely economic expediency. Over the years, food stocks accumulated in the palace could serve as a reserve fund in case of famine. At the expense of these same reserves, artisans who worked for the state were provided with food. The surplus, which was not used locally, was sold to distant overseas countries: Egypt, Syria, Cyprus, where they could be exchanged for rare types of raw materials that were absent in Crete itself: gold and copper, ivory and purple, rare breeds wood and stone.

Merchant sea expeditions in those days were associated with great risk and required large expenditures for their preparation. Only the state, which had the necessary material and human resources, was able to organize and finance such an enterprise. It goes without saying that the scarce goods obtained in this way all settled in the same palace storerooms and from there were distributed among the craftsmen who worked both in the palace itself and in its environs. Thus, the palace performed truly universal functions in Minoan society, being at the same time the administrative and religious center of the state, its main granary, workshop and trading post. In the social and economic life of Crete, palaces played roughly the same role that cities play in more developed societies.

Creation of a maritime power. Decline of the Cretan Civilization

Rise of Crete

A girl worshiping a deity. Bronze. 1600-1500 BC.

The highest flowering of the Minoan civilization falls on the XVI - the first half of the XV century. BC. It was at this time that the Cretan palaces, especially the palace of Knossos, were rebuilt with unprecedented brilliance and splendor, masterpieces of Minoan art and artistic crafts were created. At the same time, all of Crete was united under the rule of the kings of Knossos and became a single centralized state. This is evidenced by a network of convenient wide roads laid throughout the island and connecting Knossos - the capital of the state - with its most remote corners. This is also indicated by the absence of fortifications in Knossos and other palaces of Crete. If each of these palaces were the capital of an independent state, its owners would probably take care of their protection from hostile neighbors.

During this period, there was a unified system of measures in Crete, apparently forcibly introduced by the rulers of the island. Cretan stone weights, decorated with the image of an octopus, have survived. The weight of one such weight was 29 kg. Large bronze ingots that looked like stretched bull skins weighed the same amount - the so-called "Cretan talents". Most likely, they were used as units of exchange in all kinds of trade transactions, replacing money that was still missing. It is very possible that the unification of Crete around the Palace of Knossos was carried out by the famous Minos, about whom the later Greek myths tell so much. Although we may well assume that this name was borne by many kings who ruled Crete for a number of generations and constituted one dynasty. Greek historians considered Minos the first thalassocrator - the ruler of the sea. It was said about him that he created a large navy, eradicated piracy and established his dominance over the entire Aegean Sea, its islands and coasts.

Sacred bull horns. Knossos palace. 1900-1600 BC.

This legend, apparently, is not devoid of historical grain. Indeed, as archeology shows, in the XVI century. BC. there is a wide marine expansion of Crete in the Aegean basin. Minoan colonies and trading posts appear on the islands of the Cyclades archipelago, on Rhodes, and even on the coast of Asia Minor, in the region of Miletus.

On their fast ships, sailing and oared, the Minoans penetrate the most remote corners of the ancient Mediterranean. Traces of their settlements or, perhaps, just ship anchorages have been found on the shores of Sicily, in southern Italy, and even on the Iberian Peninsula. According to one of the myths, Minos died during a campaign in Sicily and was buried there in a magnificent tomb.

At the same time, the Cretans are establishing lively trade and diplomatic relations with Egypt and the states. This is indicated by the rather frequent finds of Minoan pottery made in these two areas. At the same time, things of Egyptian and Syrian origin were found in Crete itself. On the Egyptian frescoes of the time of the famous queen Hatshepsut and Thutmose III (first half of the 15th century), the ambassadors of the country of Keftiu (as the Egyptians called Crete) are represented in typical Minoan clothes - aprons and high ankle boots with gifts to the pharaoh in their hands. There is no doubt that at the time to which these frescoes date, Crete was the strongest maritime power in the entire Eastern Mediterranean, and Egypt was interested in friendship with its kings.

Disaster in Crete

In the middle of the XV century BC. the situation has changed dramatically. Crete was hit by a catastrophe, the equal of which the island has not experienced in its entire centuries-old history. Almost all palaces and settlements, with the exception of Knossos, were destroyed. Many of them, for example opened in the 60s. 20th century palace in Kato Zakro, were forever abandoned by their inhabitants and forgotten for millennia. Minoan culture could no longer recover from this terrible blow. From the middle of the XV century. her decline begins. Crete is losing its position as the leading cultural center of the Aegean.

The causes of the catastrophe, which played a fatal role in the fate of the Minoan civilization, have not yet been precisely established. According to the most plausible guess put forward by the Greek archaeologist S. Marinatos, the death of palaces and other Cretan settlements was the result of a grandiose volcanic eruption on about. Fera (modern Santorini) in the southern part of the Aegean Sea. Other scholars are more inclined to believe that the Achaean Greeks, who invaded Crete from mainland Greece (most likely from the Peloponnese), were the perpetrators of the disaster. They plundered and devastated the island, which had long attracted them with its fabulous wealth, and subjugated its population to their power. It is possible to reconcile these two points of view on the problem of the decline of the Minoan civilization, if we assume that the Achaeans invaded Crete after the island was devastated by a volcanic catastrophe, and, without meeting resistance from the demoralized and greatly reduced in number of the local population, took possession of its most important life centers. Indeed, in the culture of Knossos, the only one of the Cretan palaces that survived the catastrophe of the middle of the 15th century, important changes took place, indicating the emergence of a new people in these places. Full-blooded realistic Minoan art is now giving way to a dry and lifeless stylization, which can be exemplified by the Knossos vases, painted in the so-called "palace style" (second half of the 15th century).

Rhyton in the form of a bull's head. Chlorite. Kato Zagros. OK. 1450 BC

The motifs traditional for Minoan vase painting (plants, flowers, marine animals) on vases of the "palace style" turn into abstract graphic schemes, which indicates a sharp change in the artistic taste of the inhabitants of the palace. At the same time, graves appeared in the vicinity of Knossos containing a wide variety of weapons: swords, daggers, helmets, arrowheads and spears, which was not at all typical of the previous Minoan burials. Probably, representatives of the Achaean military nobility, who settled in the Palace of Knossos, were buried in these graves. Finally, one more fact that indisputably indicates the penetration of new ethnic elements into Crete: almost all the tablets of the Knossos archive that have come down to us were written not in Minoan, but in Greek (Achaean) language. These documents date mainly from the end of the 15th century. BC.

At the end of the 15th or the beginning of the 14th century. BC. The palace of Knossos was destroyed and was never fully restored in the future. Wonderful works of Minoan art perished in the fire. Archaeologists managed to restore only a small part of them. From this moment on, the decline of the Minoan civilization becomes an irreversible process. From a leading cultural center, as it has been for over five centuries, Crete is turning into a remote, backward province. The main center of cultural progress and civilization in the Aegean basin is now moving north, to the territory of mainland Greece, where at that time the so-called Mycenaean culture flourished.

Crete is located in the Mediterranean Sea, 100 km south of mainland Greece. It is a narrow, mountainous island, stretching from west to east, with a favorable climate for agriculture, fairly fertile soil, and excellent shallow harbors along the deeply indented northern coast. Here, having originated ca. 4000 years ago, developed, flourished and died out civilization, now known as the Minoan.

The Minoans were a seafaring people with a highly developed and complex system of religious worship and stable trading traditions. In the era when the Minoans reached their maximum power, their fleets sailed from Sicily and Greece to Asia Minor, Syria, Phoenicia and Egypt. Minoan artisans produced not only mass products, but also ceramics with amazingly beautiful paintings, and extremely diverse carved gems for religious purposes and decorations, they built magnificent palaces, and painted walls with exquisite frescoes.

The archaeological discovery of the Minoan civilization took place only in 1900, despite the fact that Greek myths and literature were from the very beginning filled with tales of the wealth and power of Crete. In Homeric Iliad at the dawn of Greek literature, King Minos is mentioned, who ruled in the city of Knossos several generations before the Trojan War.

According to Greek myth, Minos was the son of the Phoenician princess Europa and the god Zeus, who, turning into a white bull, kidnapped her and took her to Crete. In that era, Minos was the most powerful sovereign. He forced Athens to pay him regular tribute by sending young men and women who became the food of the bull-headed monster Minotaur. Athens was freed from this obligation after the hero Theseus killed the Minotaur with the help of Minos' daughter Ariadne. Minos was served by the cunning master Daedalus, who built a labyrinth where the Minotaur was caught.

In the 19th century few serious scholars believed that these legends had any historical basis. Homer was a poet, not a historian, and it was believed that big cities, wars and heroes were entirely a figment of their imagination. However, Heinrich Schliemann believed the Homeric narrative of the Trojan War. In 1873 he discovered the ruins of Troy in Asia Minor just at the place where Homer placed Troy, and in 1876 he repeated the same thing in Mycenae, the city ruled by King Agamemnon, who led the united Greek army against Troy. Homer's prestige was restored.

Schliemann's discoveries inspired the wealthy English antiquities lover and journalist Arthur Evans, who decided that since Troy really existed, then Knossos could also exist. In 1900 Evans began excavations on the island. As a result, a colossal palace and an abundance of paintings, ceramics, jewelry and texts were discovered. However, the civilization discovered was clearly not Greek, and Evans named it Minoan, after the legendary king Minos.

The emergence of the Minoan civilization.

The first inhabitants of Crete who left material evidence of themselves were farmers who used stone tools, who appeared here long before 3000 BC. The Neolithic settlers used adzes and axes from ground stone and made beautifully polished and decorated pottery. They grew wheat and raised cows, pigs and sheep. Villages appeared before 2500 BC, and the people who lived there were engaged in trade (both by sea and by land) with their neighbors, who taught them how to use bronze, probably c. 2500 BC

Early Bronze Age culture in Crete has posed a puzzle to those who have been concerned with the Minoan civilization since Evans. Many scholars continue to follow Evans and refer to this period as the Early Minoan, dating from approximately 3000 to 2000 BC. However, all excavations in Crete have consistently found that fully developed Minoan cities (such as the palace cities at Knossos, Phaistos, and Mallia) lie directly above the remains of the Neolithic culture. The first palaces in Crete, along with a new culture, suddenly arose c. 1950 BC, in the absence of any trace of the gradual development of urban culture in Crete. Therefore, archaeologists have reason to believe that we can talk about the "Minoans" only after 1950 BC, but about the so-called. early Minoan culture, it can be doubted whether it was Minoan at all.

But how did this urban revolution come about ca. 1950 BC? Probably, the Minoan civilization received an impulse from outsiders - powerful seafaring peoples who conquered Crete and established a thalassocracy here, a power based on dominance on the seas. Who these newcomers were remained a mystery until the deciphering of the Minoan script known as Linear A. The Minoan language, as revealed by Linear A, turned out to be a West Semitic language of the type spoken in Phoenicia and adjacent areas.

It is known that until the 18th century. scholars agreed with the evidence of the ancient Greeks, who spoke of their cultural dependence on the ancient Near East. For example, the Greeks called their alphabet Phoenician, or Cadmus letters - after Cadmus, the Phoenician prince, the founder of the dynasty in Thebes.

Minoan aliens were navigators from the eastern shores of the Mediterranean. They brought most of the innovations to Crete and established extensive cultural and commercial relations with the entire Mediterranean. By the end of the III millennium BC. the eastern Mediterranean became the center of world history. Along its shores, impulses from Egypt, Syria with Palestine, Mesopotamia and Asia Minor have already merged, and a whole group of peoples, extremely diverse in ethnic origin and language, formed new combinations. Such a composite culture was also characteristic of newcomers already involved in the system of trade relations. For example, Ugarit, a bustling port in northern Syria, carried on an active trade with Crete, thanks to which there was an influx of new ideas and practical skills not only from the coast of Syria and Palestine, but also from Egypt and Mesopotamia.

The personal names of the Minoan texts come from all over the Near East. Common West Semitic names found here include Da-we-da (David) and Gu-pa-nu (Gupan); the name Gupan is also found in texts from Ugarit. The Phoenician goddess Tinit appears as Ti-ni-ta. The northwestern Semitic god Yam(mu) is written here as Ya-mu. At least two of the names found on the Linear A tablets, Da-ku-se-né and Su-ki-ri-te-se-ya, are Hurrian, i.e. belong to a non-Semitic people who occupied a prominent place throughout the Middle East, from Asia Minor to Egypt, throughout the 2nd millennium BC. There are also Egyptian names such as Ne-tu-ri-Re (meaning "The sun is divine"). Minoan art reveals close ties to Egypt, with some frescoes depicting Egyptian reeds and Egyptian cats.

The Minoan religion was closely associated with Canaan. Unlike the Greek Zeus, the Cretan Zeus is born and dies like Baal (Bel) of the Canaanites. It was generally accepted that a charming goddess with her arms raised apart and her breasts bare, dressed in a frilled skirt, headed the local pantheon in Minoan Crete. Prior to the decipherment of Linear A, such interpretations, as a rule, did not raise objections. However, an extremely important result of archaeological excavations was overlooked. There are absolutely no cult statues in the palace sanctuaries; moreover, there is not even a pedestal on which such a statue could be placed. Archaeological evidence from Jewish sanctuaries indicates that the results of excavations in Crete may be interpreted differently. The Minoan U-shaped "horns of initiation" cannot be separated from the Jewish altar horns mentioned in Psalms 117, 27 and preserved in the corners of the stone altars of excavated Jewish sanctuaries. Archaeologists have found statuettes depicting the naked fertility goddess Astarte in the homes of ancient Jews up to the period of the destruction of the first Temple (586 BC). However, we know from the Bible that the official cult of Yahweh was aniconic (i.e., not associated with images), and no cult statues of Yahweh (identified with El, head of the Canaanite pantheon) have been found. While the Minoans are more polytheistic than the ancient Hebrews, Linear A tablets found at Agia Triada suggest that most of the sacrifices were not to goddesses but to the male deity A-du (pronounced "Ah-duu" or "Hah -duu"), which in the Ugaritic texts was another name for Baal, the most active god in the Canaanite pantheon.

IN Theogony Hesiod The first king of the gods was Uranus, who was replaced by Kronos. This latter gave birth to Zeus, who succeeded him, who was born on Mount Dikta in Crete. The prototype of this genealogy is the Hurrian myth of Kumarbi. Since Hesiod's account has a Hurrian source, since he places the birthplace of Zeus in Crete, and since myths usually carefully preserve the names of places, it is clear that this tale was not brought to Greece by travelers or visiting merchants, but arrived with the Hurrians who settled in Minoan Crete.

Throughout their glorious history, the Minoans have experienced both ups and downs to the fullest. Outside the Aegean Sea basin, 11 colonies belonging to them are known, widely spread across the eastern and central Mediterranean. During the excavations, their palaces were discovered in the eastern part of Crete - in Knossos, Phaistos, Mallia and Zakro. Minoan finds (including also texts) made near Chania suggest that there was a palace in the west as well. Objects belonging to the Minoan civilization have also been found on other islands of the southern Aegean, primarily on Thera, Melos, Cythera, Keos and Rhodes.

The excavations carried out on Fera are of the greatest importance. As a result of a volcanic explosion in the middle of the II millennium BC. the middle of the island disappeared, and the rest of it was covered with volcanic ash, which buried the city that existed here. The catastrophe that befell the Minoans kept intact significant fragments of their culture. The frescoes on Fera are extremely remarkable. Particularly noteworthy is the image of the ships, which shows both a pleasure boat trip of the nobility and a warship in the heat of battle.

Judging by the inscriptions from which we draw information about the life of Crete, it seems doubtful that the vast Minoan "empire" was ruled from a single center. Much more plausible is the assumption that the Minoan power was formed by a confederation of city-states, such as Knossos, Mallia and Festus. We know the names of several kings, the most famous of which was Minos. This name was borne by at least two kings, and it is possible that the word "minos" became the general designation of the ruler.

Although the center of the Minoan civilization was Crete, this culture spread to many of the islands and coastal areas of the Aegean and the Mediterranean in general, as well as to at least one inland region beyond the Jordan. The powerful culture of navigators is not amenable to precise localization: evidence of archeology, and in some cases written sources found in very remote lands, speaks of the relationship that the Minoans maintained with areas of Greece, Asia Minor, Cyprus, Syria, Palestine, Egypt, Babylon and others countries. Most of the Minoan graphic images found outside the sphere of the Minoan civilization are concentrated in Egypt. So, on the paintings in the tomb of Senmut, the architect and confidant of Queen Hatshepsut (ruled c. 1503-1482 BC), Minoans are depicted bringing gifts.

The Minoans were active in trade, their numerous merchant fleet went to sea with valuable cargo - ceramics, metal products, wine, olive oil, to exchange them overseas for copper, tin, ivory and gold. The Minoan trading ships had, as a rule, a high bow, a low stern, and a keel protruding backwards. They were set in motion by rowers sitting in two rows and a sail.

The successes of the Minoans in the field of military affairs were not limited to the fleet. For a long time, the Cretans were famous as skilled archers and slingers. Their compound bow was so well known that texts from Ugarit say that it was made by the god Kotar-va-Khasis in Crete.

Gen.

Judging by the fine arts of the Minoans themselves, they were graceful and cheerful people. Long hair was worn by both men and women, but women decorated it in a particularly diverse way, styling it with curls and curls. The clothes of men consisted practically only in a wide leather waist belt and a leather codpiece. Women wore long and colorful skirts with frills, as well as a bodice that left their arms and chest bare.

The urban community was made up of the upper class (which included the royal family, nobles and priests), the middle class and slaves. As can be assumed, according to the position in society, women were equal in everything to men, they participated in all types of activities, including the most dangerous types of athletic pursuits. Farmers who lived in the countryside grew wheat and barley, as well as olives, almonds and grapes. In addition, they produced wool and linen for the production of fabrics. In the cities there were refined craftsmen, carvers of precious stones and ivory, painters, goldsmiths, stone vases and goblets makers. Dancing and athletics, such as fisticuffs, were popular. The main sport was bull jumping. A young man or woman stood in front of an attacking bull and grabbed him by the horns; when the bull tossed his head, the jumper did somersaults over the horns, pushed off with his hands from the bull's back, and landed on his feet behind the bull.

The most complete picture of the life of the Minoan Crete was given by archaeological excavations carried out in Gournia, a city in the eastern part of Crete. A palace, a square for public events, a sanctuary, as well as a characteristic labyrinth of houses built from rubble stone and mud bricks were discovered here.

Religion.

The Minoans worshiped many gods, some of which can be traced back to ancient times. Our knowledge of these gods is scarce, but by noting similarities with more famous gods in other regions of the Near East, it is possible to draw conclusions about the Cretan gods themselves and the nature of worship. Thus, in the mountain sanctuaries they worshiped the widely revered god (Y)a-sa-sa-la-mu (pronounced "ya-sha-sha-la-muu"), whose name means "He Who Gives Well-being." At least six Minoan cult objects are dedicated to him - stone tables for libation, etc.

The most widely known Minoan deity is the goddess, usually depicted in a frilled skirt, with her arms raised outstretched to the sides, and snakes are often wrapped around her body and arms. Her figurines became a symbol of the Minoan civilization. This goddess, like Yashashalam, may also be of Semitic origin, as she appears on cylinder seals from Mesopotamia, earlier than those from Crete. Sometimes Minoan artists depicted her standing on a mountain surrounded by animals.

The name Dagon, mentioned in the Bible as the god of the Philistines, appears on Minoan tablets in the form Da-gu-na. This is also a widely revered Semitic deity: Ugaritic myths call him the father of the fertility god Baal. Some beliefs, common in Minoan Crete, lasted until antiquity. Hesiod and other Greek poets mention myths that say that the god Zeus was not only born in Crete, but died and was buried there. The story of Zeus's usurpation of his father Kronos is almost exactly parallel to the myth of the Hurrian storm god Teshub, who deposes his father Kumarbi in exactly the same way. Hesiod associates this event with Crete, and his account includes many of the unsightly details of the original, leaving no doubt as to the source of the later myth.

A common feature characteristic of the Minoan religion was the worship of nature - sacred trees, springs and stone pillars.

Unlike many ancient inhabitants of the Middle East, the Minoans did not erect majestic temples to their gods. Joint cult actions were performed by them on palace sites, in cave sanctuaries, in house temples, in chapels built over the sources of streams, but primarily in sanctuaries on the peaks. Small temples built on mountain tops are a characteristic feature of the Canaanite religion, they can be compared with the "high hills", which, in connection with the practice of worship that existed on them, are furiously attacked by the prophets of Israel.

The bull played an important role in the Minoan religion. In the Greek myths associated with Crete, events often unfold around a bull, as in the case of the abduction of Europa by Zeus or in the legend of the Minotaur. Minoan altars and roofs of sanctuaries often had horn-shaped protrusions, which may have come from the horns of a sacred bull and were commonly called horns of initiation. Even the Minoan bull-jumping had, in addition to the athletic, also a religious side.

Art.

Minoan art is the most joyful and radiant of all the ancient arts. In the relief image of a vase from Agia Triada, we see the procession of farmers at the harvest festival. A typical Minoan detail on this vase is an image of a reveler knocked down by hops, who buried himself in the ground and sleeps.

Minoan frescoes invariably amaze with freshness and naturalness. Boys and girls carelessly jump over the horns of bulls rushing at them; a Cretan goat gallops over the rocks; dolphins and flying fish glide through the waves.

An important artistic convention introduced by the Minoans was the depiction of galloping animals. This technique, which so successfully allows you to depict the swiftness of movement, spread from here to Egypt, Persia, Siberia, China and Japan. The Minoans also used static patterns - zigzags, cross-hatching and other linear means known from Middle Eastern painted pottery.

Bright, saturated colors were used in Minoan art not only on frescoes, but also in architecture, and on ceramics made on a potter's wheel. The fact that the Minoans often painted men red and women yellow was not just a convention. Following a widespread custom in antiquity, Minoan men painted their bodies red for ceremonial purposes, while women painted themselves yellow. This is how people are depicted on the sarcophagus from Agia Triada, where they carry calves and other gifts and play the lyre on the occasion of the funeral of the prince.

In addition, the Minoans produced an extremely diverse range of pottery, seals, stone vessels, metal tools, and jewelry, thus continuing the indigenous craft traditions that preceded the heyday of the Minoan civilization.

Architecture.

The most remarkable examples of Minoan architecture we find among the remains of the palace cities, such as Knossos and Mallia in the north, Phaistos and Agia Triada in the south of Crete. The Minoans, in fact, did not engage in urban planning. The head of the community chose the best place for his palace, and his relatives and retinue built houses around the palace. For this reason, cities had a radial layout, with streets starting from the palace in the center and connected by more or less concentric lanes.

Palace cities were usually located inland, and were connected to port cities by paved roads. A notable exception to this rule is Mallia: the coastal plain here is so narrow that Mallia was also a port.

The largest Minoan palaces are colossal labyrinthine systems of rooms; perhaps they served as a model for the labyrinth of the Minotaur. This "accumulative" principle of construction has become characteristic, probably since the late Neolithic, when the first villages appeared on Crete. The Minoan buildings were several stories high (as they are preserved on Thera) and flat roofs. Palaces could be built of hewn stone, but the lower floors of ordinary houses, as a rule, were built of raw stone. Raw brick was used for the upper floors, sometimes even during the construction of the palace. In some cases, to provide at least partial protection against earthquakes, the walls of the palaces were reinforced with interlacing wooden ties.

Among the Minoan palaces, the most famous is Knossos (Palace of King Minos). The original appearance of the palace is guessed by the appearance that the palace acquired ca. 1700 BC when it was destroyed by an earthquake or a series of earthquakes and then rebuilt. The palace, built around a large rectangular open courtyard, was almost square in plan, each side measuring ca. 150 m. Halls and front rooms were located at least two floors above the courtyard. A beautiful and majestic staircase formed by many flights, built after the first destruction of the palace, led from these chambers down to an open courtyard, on the sides of which were erected two rows of rather short columns, smoothly tapering from a wide top to a narrow base. The light well in this courtyard is a typical Minoan solution to the problem of illuminating a large number of interior spaces. A paved road leading from the palace was thrown over a deep ravine by a viaduct of huge boulders and connected with a large road that crossed the island, which led from Knossos to Phaistos.

In the Throne Room stands a unique gypsum throne, flanked by frescoes depicting griffins. The wooden throne once stood in the Hall of Double Axes located in the residential part of the palace (so named because a mason's mark was found on the stones of its light well - an ax with two blades). In fact, it was a deep portico, facing east. A narrow passage leads from it to a small, elegantly decorated room, called the Queen's Megaron, with two wells of light - on the west and east sides. Next to it there was a small pool for ablutions, and along a long corridor one could get to the toilet room: water supply and sewerage were brought here.

The earthquakes that destroyed the palace of Knossos did not cause significant damage to the palace in Mallia, and therefore its rebuilding was much less significant. The Phaistos Palace, which was erected between 1900 and 1830 BC, was so damaged by earthquakes ca. 1700 BC, that they did not even begin to restore it, it was simply abandoned, and a new palace was built nearby, in Agia Triada.

Writing and language.

The earliest Cretan writing is pictograms, usually on clay tablets, dating back to around 2000 BC. These pictograms are called Cretan hieroglyphs. They seem to be mostly of local origin, although some symbols are similar to those of Egypt. A special and unique pictographic letter, presumably of a later type, we find on the so-called. Phaistos disk, a round clay tablet (diameter 16 cm), on both sides of which pictograms are squeezed out with the help of seals. The future decipherment of the linear script associated with these pictograms raises hopes for a solution to the disc riddle.

The hieroglyphs were replaced by a linear script developed from them, at Knossos this happened ca. 1700 BC, in Phaistos somewhat earlier. This script, which is called Linear A, still retains traces of its pictographic origin; it is found on a number of clay tablets dating from 1750 to 1400 BC.

Around 1450 BC at Knossos, along with Linear A, Linear B began to be used. Texts written in Linear B were also found in mainland Greece, and this led many scholars to believe that some form of Greek corresponded to this script.

The topics to which the Minoan texts are devoted, written both on clay tablets and on stone cult objects, are mainly economy and religion. About 20 cult objects come from different places scattered throughout central and eastern Crete. More than 200 household tablets, mostly receipts and inventories, were found in several places in the eastern half of the island. Far superior to any other collection of tablets from Agia Triada - c. 150 household and administrative clay documents.

The Mycenaeans and the Decline of the Minoan Civilization.

At some point after 1900 B.C. from the Balkan region, or perhaps from more distant regions to the east, Greek-speaking peoples invaded mainland Greece. Spreading from Macedonia to the Peloponnese, they founded many cities, such as Pylos, Tiryns, Thebes and Mycenae. These Greeks, whom Homer calls Achaeans, are now called Mycenaeans.

The warlike Mycenaeans were at first relatively uncivilized, but from about 1600 B.C. they entered into various relations with the Minoans, as a result of which their culture on the continent underwent dramatic changes. Period from 1550 to ca. 1050 BC in Crete some scholars call Late Minoan. Around 1400 BC The Mycenaeans took possession of Knossos, and from that moment Crete was the birthplace of the combined Minoan-Mycenaean culture. With this date and the following two or three centuries, we primarily associate Linear B: the Mycenaean Greeks adapted the Cretan script to their own language.

Between 1375 and 1350 BC the power of the Minoans was undermined. The eruption at Thera covered eastern and central Crete with a thick layer of volcanic deposits, rendering the soil barren. The eruption also caused a devastating tidal wave that caused a lot of trouble not only in nearby Crete, but throughout the eastern Mediterranean. Another factor that contributed to the decline of the Minoans was the constant influx of Mycenaeans from the continent.

Mycenaean culture continued to flourish. The Trojan War took place ca. 1200 BC, and Homer mentions that King Idomeneo of Crete arrived with a force of Mycenaeans to help the Greeks. The collapse of the Mycenaeans occurred around 1200 BC, when they were defeated by the invading Dorians, the last Greek-speaking people who came to Greece from the north, after which Greece itself and Crete entered the so-called period. "Dark Ages", which lasted over 300 years.

Whatever the details, it seems that the collapse of the Minoan and Mycenaean cultures provoked a series of mass migrations of the so-called. "Sea Peoples" who crushed the Hittite power in Asia Minor, threatened Egypt and changed the course of history in the Middle East. One of the most important among these migrations is that of two Aegean peoples known to history as the Philistines and the Danites, who threatened the Nile Delta during the reign of Pharaoh Ramesses III (c. 1194–1162 BC). The Egyptians eventually repulsed this attack, after which these peoples went to the northeast to settle on the southern coast of Palestine (the word is a derivative of "Philistia").

The Philistines constantly fought with the Jewish tribes, but the Danites broke away from them and moved into the depths of the continent, subsequently they united with the Jews, forming the tribe of Dan. The Philistines and Danites, once allies, became hardened enemies. Samson, the greatest Danite hero in the fight against the Philistines, appears in the Bible as one of the "judges" of Israel.

Minoan history has a very curious afterword. In the two cities of eastern Crete, Pres and Drer, pockets of Minoan Semites survived, who lived side by side with their Greek neighbors. Two linguistically distinct communities in both cities left inscriptions. Scholars have given the non-Greek language a proper name: "Eteocretan", which means "genuinely (or originally) Cretan". Both inscriptions are composed using the same familiar letters of the Greek alphabet. Among the inscriptions from Drer there are two Eteocretan-Greek bilinguals. Eteocretan texts date from ca. 600–300 BC Back in Roman times, it was widely known that the old non-Greek language in Crete was a Semitic language. In a literary hoax related to the 4th century. AD, notes on the Trojan War Dictys of Crete, allegedly a companion of the Cretan king Idomeneus, it is alleged that their original, written in "Phoenician letters", was found by shepherds in the tomb of Dictis near Knossos. This is the last fragment of the Minoan civilization that has come down to us.

MINOAN CULTURE - ar-heo-logical cul-tu-ra [mid-4th millennium - XII century (mainly until the XV century) BC. e.] on the island of Crete, connected with the ancient neck qi-vi-li-for-qi-her on the ter-ri-to-rii of Europe.

Previously, it was ras-smat-ri-va-las within the framework of the Aegean culture. Opened at the beginning of the 20th century by A. Evansom, who called it by the name of King Mi-no-sa. Evansom pre-lo-same-but you-de-le-nie (mainly on the basis of the change of styles ke-ra-mi-ki) in the Minoan culture of 3 periods ( early-non-, medium-non-, late-non-mi-noy-sky) with sub-raz-de-le-ni-em into phases; this scheme (with kor-rek-ti-va-mi) is used by pain-shin-st-vom research-to-va-te-lei. According to another chrono-logical system, pre-lo-wife by the Greek ar-heo-log N. Pla-to-nom (os-no-va-na on the blue-de- ni-yah over the evolution-lu-qi-ee of architectural complexes), you-de-la-yut-sya 4 period-yes: before-, pro-to- (early-), neo - (but-in-), after-yard-tso-vyy (post-le-dvor-tso-vyy, for Knossos - after-yard-tso-vyy).

In the early-not-mi-noy-sky per-ri-od kul-tu-ra Kri-ta in a row in-ka-for-te-lei from-hundred-va-la from neighbor-kul -tour. At the end of the period, yes, fik-si-ru-et-sya increase the number of-len-no-sti on-se-le-niya, the appearance of large in-villages, rise of re-mes-la, in-ten-si-fi-ka-tion of long-distance connections, would you include in someone-rye Per-red -nyaya Asia, Egypt and other lands. The orb-tu of the influence of the Minoan culture includes a number of islands of the Aegean Sea. In the middle-Mi-Noi-sky period (from the end of the 3rd - the beginning of the 2nd millennium), large centers appear (Knossos, Fest, Mal- liya, etc.), wi-de-tel-st-vuyu-schi about the for-mi-ro-va-nii of state education. At the end of the middle-not-mi-noy-sko-th period-yes and at-cha-lo late-not-mi-noy-go-go period-yes -yut not-od-vor-tso-in-mu-pe-rio-du; XVII - the middle of the XV centuries) come-ho-dyat-su-shche-st-ven-nye from me-ne-niya in the structure -tu-re cul-tu-ry and its race-color. Crete, ve-ro-yat-no, ob-e-di-nya-et-sya under the head of Knossos and become-but-vit-sya the strongest sea power howl, in the place of the old ones, there are new courtyards, complex complexes, arranging a network of so-ho-way roads . Around 1450, many centers of the Minoan culture perished in ka-ta-st-ro-fe, in a vi-di-mo-mu connected with the earth-le-trya-se-niya-mi, syn-chron-ny-mi from-ver-the-same-nyu vul-ka-na on the island of San-to-rin. Later (about-lo-ru-be-zha of the XV and XIV centuries, there are other yes-ti-ditches) on Cree-te ras-pro-country-nya-et-sya mi-ken-skaya kul-tu -ra, which is connected with the way-wa-ni-em of his ahey-tsa-mi, the traditions of the Minoan culture for-to-ha-yut.

The social system of the mi-noi-sky qi-vi-li-zation, at least in the new-court-ts-vy period, was based on the exploitation -ta-tions of the rural-on-se-le-tion with the teaching of the whole-ma-ma-of-that bureau-ro-cratic system-te-we. At the head of the go-su-dar-st-va stood the monarch, who had a wide circle of close wives, some va-te-li consider that his power had a theo-cratic character. You-de-la-et-sya female god-same-st-in, ve-ro-yat-but the former neck of the central fi-gu-swarm pan-te-o-na. An important role was played, apparently, by God in the form of a bull or a man with a bull's head; the cults associated with him were also reflected in the Greek myths about Mi-no-tav-re. Among the reasons for the races of the color of the Minoan culture, a number of studies-follow-up-va-te-lei on-zy-va-yut trade-lyu with tin, not-about-ho-di-my for po-lu-che-niya ka-che-st-vein bronze, the most important ma-te-ria-la of the epoch. From the early-not-mi-noi-sko-go period-yes fik-si-ru-et-sya in-yav-le-nie "ko-lo-niy" of the Minoan culture on the Kiklad Islands, the island of Rhodes, in the district of Mi-le-ta. Later, from de-lia, associated with the Minoan culture, become-but-vyat-sya from the West from Me-so-pot-mia on the east-ke to on-be-re -zhya Pi-renais-sko-th peninsula on the pas-de. Within the framework of the Minoan culture, an ancient-shay appeared in Ev-ro-pe writing-men-ness (see the Cretan letter), about-is-ho-dit the color of ar-chi -tech-tu-ry, fresco-howl zhi-vo-pi-si, va-zo-pi-si, plastic arts (see the article Aegean art-kus-st-vo). The Minoan culture of the eye-for-la su-sche-st-ven-noe influence on the development of the Myken-skay and a number of other cultures of the Eastern Middle-di-earth-but-sea .

InIImillennium BC. e. Minoan civilization existed on the island of Crete. For the first time, Robert Pashley began to collect information about it, and Arthur Evans finally confirmed the existence of civilization, who seriously took up the Knossos Palace. Before this epoch-making event, scientists were separated by years of delusions, when the Minoan civilization was not perceived as isolated - it was simply called the predecessor of the Mycenaean civilization.

History of the Minoan Civilization

As the civilization was studied, it received its own name - Evans called it Minoan, in honor of King Minos. The descendants of the Minoans may have been the Eteocretans (or true Cretans) about whom Homer wrote. The main centers of Minoan culture were palaces - economic and political centers in Zakros, Knossos, Phaistos and Tiliss. Each of the palaces found and studied has unique features, but all have common features. So, Minoan palaces were monumental and multi-storey structures with courtyards and massive columns.

It is reliably known about the Minoans: they had a huge influence outside Crete - many handicrafts brought from the island were found on mainland Greece. The Minoans established trade relations, including with Egypt, from where they brought architectural ideas and papyrus to Crete. They maintained relations with the islands of the Cyclades, Syria and Mesopotamia. Until now, frescoes and other artifacts of the Minoans continue to be found in different places - in Cyprus, in Anatolia and even in Israel. All this indicates a high level of organization and a desire to establish contacts with other peoples.

In the Eastern Mediterranean, the Minoan fleet had no equal: it unconditionally influenced all processes, founded colonies and fought pirates. As a result, the power of the fleet and success in shipbuilding reached such unattainable proportions that modern researchers call Minoan Crete a maritime state. Of course, the successful location of the island at the crossroads of important sea routes served as a source of prosperity.

The prosperity of civilization was disrupted by a natural disaster: the eruption of the Tyra volcano. The earthquake wave reached the shores of Crete and led to irreversible consequences. Residential areas and the most important palaces were destroyed. Only Knossos remained almost untouched - later a dynasty was born here that influenced the life of Crete before the arrival of the Mycenaeans. Having captured the island, they adapted the linear writing of the Minoans to the needs of their own language.

Today it is impossible to say exactly what was connected with the death of the Minoan civilization- the most developed in ancient Europe. Whether the decline was associated only with an earthquake or the invaders had a hand in the disappearance - this remains to be seen.

Minoan culture: a legacy of civilization

From the Minoans, modern Greeks inherited numerous archaeological finds. These people had a great sense of form, as can be judged from the cups, vessels in the form of animal heads, jugs and figurines. If the ancient inhabitants of Crete created an image of a person, they never made a static pose - they perfectly conveyed movement. Carvings made of stone, ceramics of various types and skillfully executed frescoes have come down to us. The largest collection of Minoan heritage today can be seen in the museums of Heraklion.

The religious views of the Minoans are well studied. They worshiped mostly goddesses - the culture was built on matriarchy. Images of deities in various guises were widely used: the mistress of animals and cattle, the goddess of fertility, harvest, household, cities, the underworld. Goddesses were depicted with birds, snakes or animals on their heads.

The Minoans had an excellently developed agriculture. They not only raised cattle and grew crops, but also domesticated bees, cultivated olives and grapes. It is also known that the Minoans actively hunted wild boars and birds. The variety of products has led to the growth and improvement of the health of the Cretan population.

Not the last role in the prosperity of the Minoan civilization was played by writing. The Minoans own the most ancient hieroglyphs found in Crete. No one knows if the locals had a special language or whether they borrowed writing from Mesopotamia and Egypt. Hieroglyphs have long been used in parallel with Linear A.

Today, tourists are immersed in the Minoan past of Crete with interest. But in an effort to see the Palace of Knossos, one should not forget about dozens of other monuments of this civilization. On the hillside near Mirabello Bay are the remains of the settlement of Gournia, which had a small palace. From the early Minoan period, the foundations of the city of Pyrgos remained. And on the road from Ierapetra to Agios Nikolaos, you can get to the excavations of Vasiliki - a unique settlement that dates back to the pre-palace period.